US Historical

Context

ABOUT

While Perspectives of Change focuses on the history of Harvard Medical School, the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, and their faculty, students, trainees, and alumni, as well as on the history of medicine in Boston, the context of American history provides background and connection to the project.

1619-1799: The First Enslaved Africans in the American Colonies to Abolition of Slavery in Massachusetts

In August 1619, a Portuguese ship carrying 20 enslaved Africans landed in Port Comfort, part of the British Colony of Virginia. Historians estimate that between 12 million to 12.8 million Africans were forcibly moved from Africa across the Atlantic during the Transatlantic slave trade from the 16th to the 19th century.

The first medical school in the United States was founded in 1765 at the College of Philadelphia by John Morgan and William Shippen, Jr. The school is now the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

After the American Revolution, Massachusetts abolished slavery, but there is no definitive date or moment when slavery was abolished because it was slowly phased out in the state. Prior to the 1780s, a person could be freed from slavery by manumission, buying their freedom, suing for freedom, or running away. A group of slaves petitioned the colonial government for freedom after the Revolutionary War without success, but two court battles in response to the Massachusetts Constitution led to the end of slavery in Massachusetts.

See “African Americans and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts,” Massachusetts Historical Society, for more information: http://www.masshist.org/endofslavery/index.php?id=61.

The Three-Fifths Compromise was reached among state delegates during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. It determined that three out of every five slaves were counted when determining a state’s total population for legislative representation and taxation. Before the Civil War, the Three-Fifths Compromise gave a disproportionate representation of slave states in the House of Representatives.

1800-1865: Antebellum Period Through the Civil War

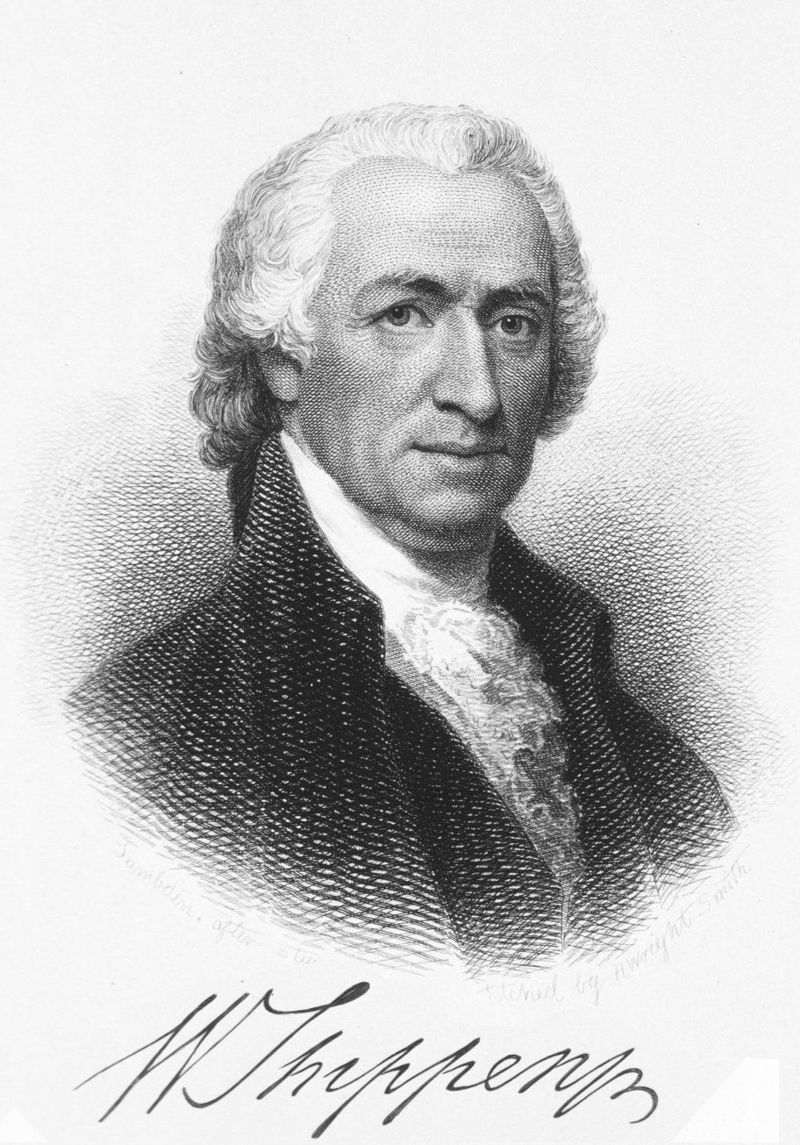

James McCune Smith was born into slavery in 1813 in New York City. He gained emancipation in 1827, and attended the University of Glasgow in Scotland where he earned his bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and medical degree. He returned to New York to set up his own medical practice in 1837.

Elizabeth Blackwell earned her medical degree from Geneva Medical College in 1849, thus becoming the first woman to receive an MD from an American medical school. She died in 1910 after practicing medicine for many years.

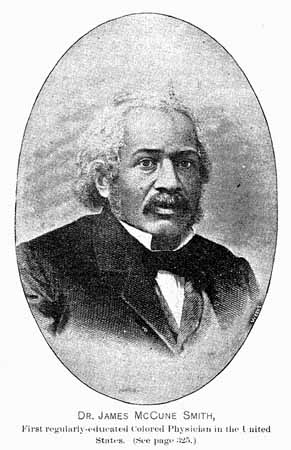

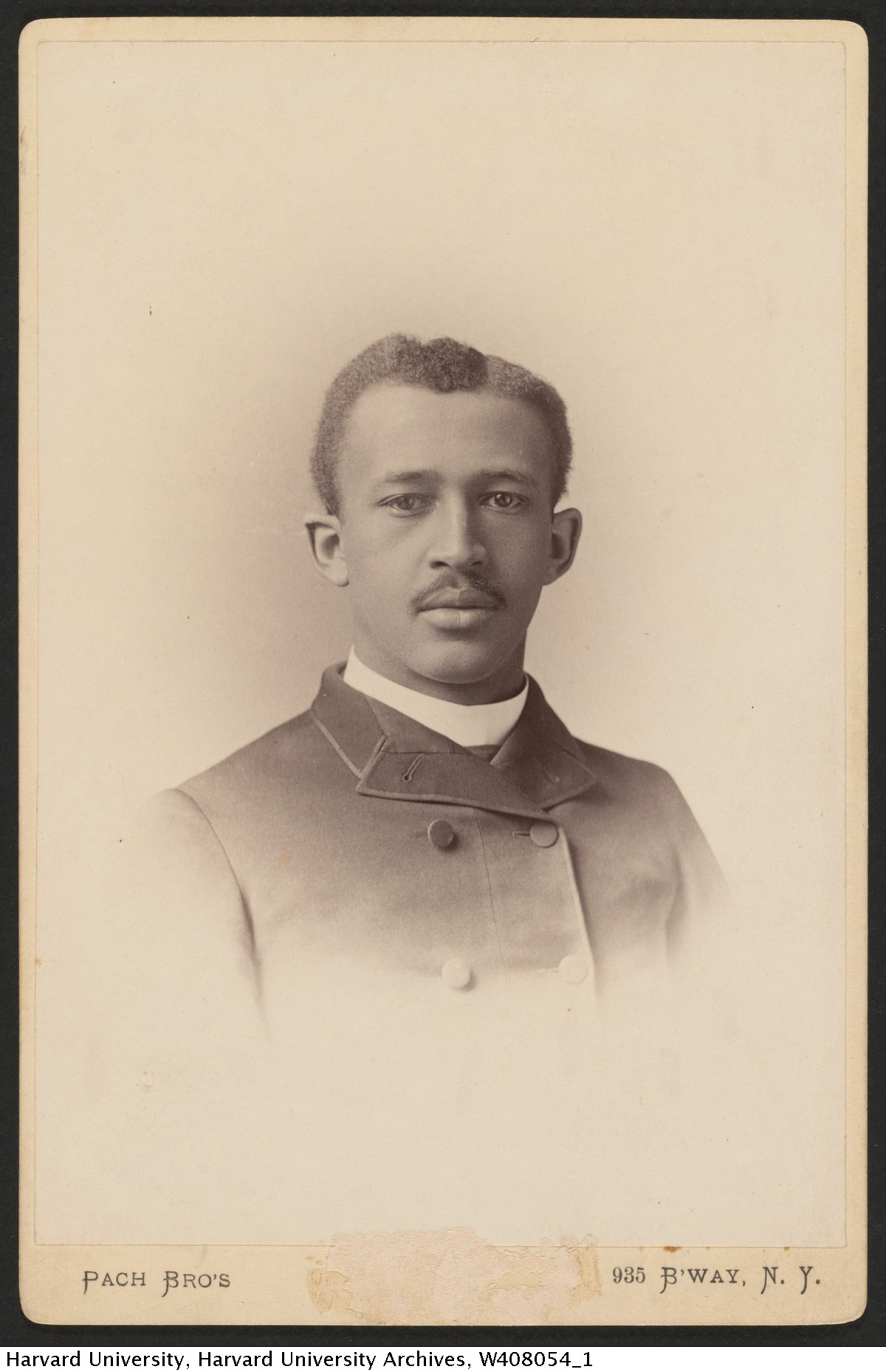

1849: David Jones Peck, MD Becomes the First African American Physician Trained in the United States

John Peck was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He studied medicine under Dr. Joseph P. Gaszam in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated from Rush Medical College in Chicago. He established his practice in Pennsylvania in 1849.

Roberts v. Boston was an 1850 court case which was cited by Plessy v. Ferguson, upholding the “separate but equal” standard. Benjamin F. Roberts, an African-American man, sued the city of Boston after his daughter, Sarah C. Roberts, was denied admittance to whites-only schools in her neighborhood. The Supreme Court of Massachusetts heard the case and ruled in favor of Boston.

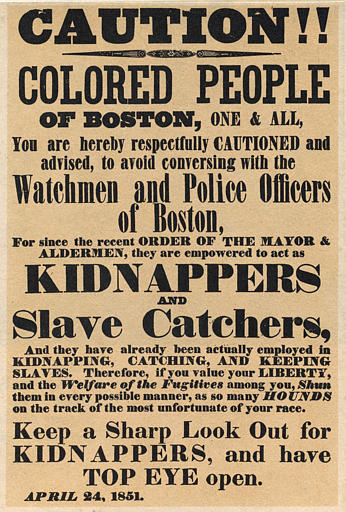

The Fugitive Slave Act was passed by the United States Congress in September 1850. It required that all escaped slaves must be returned to their masters, and that citizens of Free states must not hinder the activities of Federal marshals in capturing escaped slaves.

Dred Scott v. Sandford was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court upholding that the Constitution of the United States was not meant to include American citizenship for Black people.

Dred Scott, who was born into slavery in Virginia around 1795, sued Irene Emerson for his freedom in 1846. Scott argued that he and his wife should be granted freedom because they had lived in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory (where slavery was prohibited) for several years. Scott v. Emerson was tried in 1847 in Missouri. Evidence presented by Emerson was ruled to be hearsay, and in a retrial, the jury ruled in favor of Scott’s freedom. Emerson appealed the verdict, and the Missouri Supreme Court struck down the lower court ruling, arguing that Missouri did not have to defer to the laws of free states.

In 1853, Scott sued for his freedom under federal law. Emerson had moved to Massachusetts, and transferred Scott to her brother, John F. A. Sanford. Scott lost in federal court, and appealed to the Supreme Court. In 1857, the Supreme Court found that Scott, nor any other person of African descent, could claim citizenship in the United States and therefore could not bring suit in federal court. It also voided ordinances and acts that imparted freedom or citizenship to non-white people in territories.

Despite losing his suit, Scott and family were manumitted on May 26, 1857.

The American Civil War, also referred to as the War of the Rebellion, was fought from 1861 to 1865 between the North (the Union) and the South (the Confederacy). The war was fought over the enslavement of Black people in America. A monument to Harvard Medical School's Union Soldiers and Sailors who gave their lives for freedom, hangs in Harvard Medical School's Gordon Hall and reads:

"To the Memory of the Graduates and Members of the Medical School of Harvard University who fell in the Army and Navy of the United States during the War of the Rebellion.

Erected by the Class of 1869-70

- John Lawrence Fox

- Charles Henry Wheelwright

- Samuel Lee Bigelow

- Edward Hutchinson Robbins Revere

- William Henry Heath

- Samuel Foster Haven

- Robert Ware

- Lucius Manlius Sargent

- Ira Wilson Bragg

- jJohn Edward Hill

- Dixi Crosby Hoyt

- Henry Sylvanus Plympton

- Edward Bromfield Mason

- John Fletcher Stevenson

- William Borrowe Gibson

- Neil K Cunn

- James Witchman

- Eugene Patterson Robbins

- Henry Livingston Dearing

- Nathaniel Bowditch

- Oliver Dean Root"

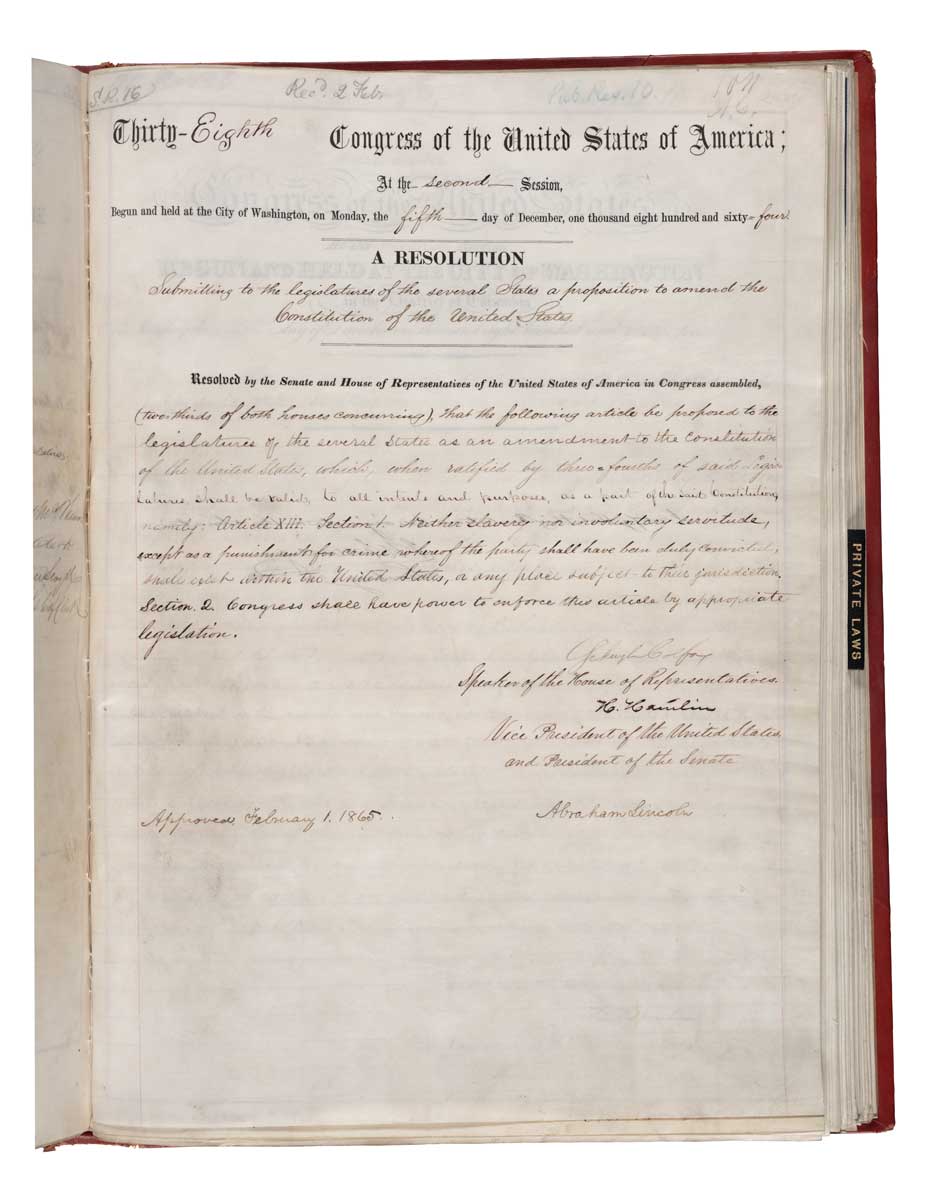

Amendment XIII to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment when a person has been convicted of a crime. The XIII Amendment was passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the states on December 6, 1865. In 1868, Amendment XIV gave Black people equal protection under the law and in 1870, Amendment XV granted black men the right to vote.

On June 19, 1865, news arrived in Texas that slavery was abolished. This occurred two-and-a-half years after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation declaring that all slaves in the states engaged in rebellion against the Union were free. Enslaved Africans in Texas were the last slaves in the states fighting against the Union to receive word of their freedom.

Major General Gordon Granger led Union Soldiers into Galveston and issued General Orders Number 3 on June 19th, which read, in part:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, "all slaves are free." This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

One year later in 1866, freed Africans in America began what is now an annual celebration of their independence from slavery. Today, Juneteenth (a blend of the words June and nineteenth) festivals and events marking the independence of enslaved Africans in America are increasing throughout the U.S. as calls rise for Juneteenth to be recognized as a national holiday.

Harvard Medical School held its first Juneteenth program on June 19, 2020.

For more information on Juneteenth, visit: https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/what-is-juneteenth/

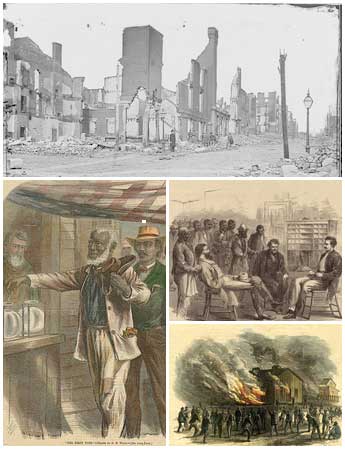

During the Reconstruction era from 1865-1877, following the Civil War, Confederate States were required to take an oath of loyalty to the Nation and to abolish slavery in order to be admitted back into the Union. Northern “carpetbaggers” and federal troops occupied the South to protect the Civil Rights of African-Americans. The Freedmen’s Bureau, established in 1865 and abolished in 1872, provided assistance to emancipated slaves, while Southern states passed “black codes” to restrict the rights of emancipated former slaves. Reconstruction saw the rise of Black participation in politics, including the House of Representatives, and the US Senate, as well as the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and other organizations and tactics to intimidate, threaten, and harm, African-Americans.

1866-1895: Reconstruction Through the Rise of Jim Crow

The Civil Rights Act of 1875 was a United States federal law enacted during Reconstruction. It was designed to protect all citizens in their civil and legal rights, and was the last major piece of legislation related to Reconstruction passed by Congress. The act forbade discrimination in hotels, trains, and other public spaces. It was declared unconstitutional in 1883, as protection against discrimination was not authorized by the 13th or 14th Amendments of the Constitution.

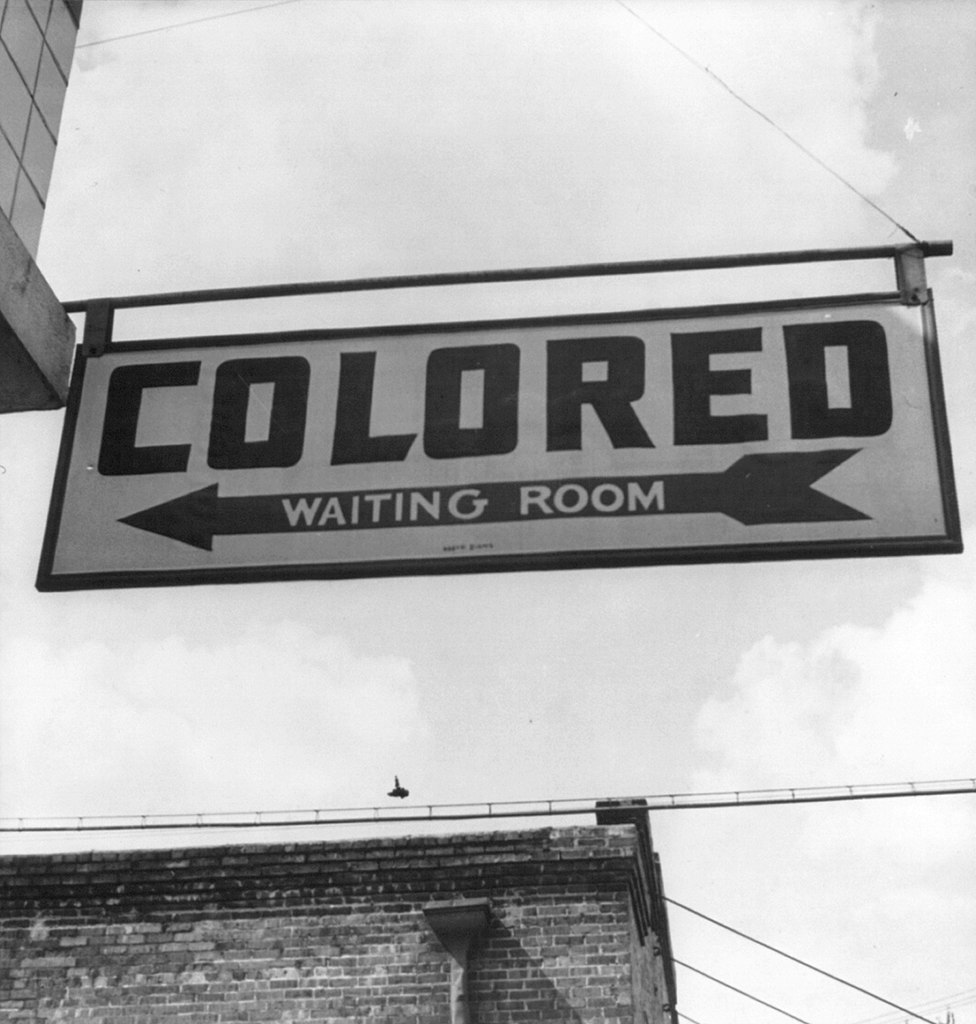

Jim Crow Laws were state and local laws enforcing segregation in the United States. Enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and enforced through 1965, these laws mandated segregation in public facilities like schools, restrooms, restaurants, and drinking fountains in former Confederate States, and included transportation like interstate buses and trains. Segregation of public schools was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in Brown v. Board of Education, and the remaining Jim Crow laws were overruled by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Thomas William Patrick was born in Haiti in 1872 and raised in Trinidad, West Indies. There, he studied pharmacy for six years as an apprentice, beginning in 1885, and acquired his license in pharmacy. Patrick settled in Boston, Massachusetts after immigrating to America in 1892. Three months later, he took and passed the Massachusetts State Board of Pharmacy examination, becoming one of the few Black pharmacists in the country. That same year, Patrick not only began tutoring students preparing to take the state board examination in pharmacy, but also formally established the Patrick School of Pharmacy, located at 19 Essex Street in downtown Boston. Patrick went on to establish his own apothecary and earn a Doctor of Medicine degree from the Boston College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1894. He relocated his school twice before establishing it in his house on Centre Street in Roxbury in 1920. Dr. Patrick closed the Patrick School of Pharmacy in 1937.

Medical professional associations and societies are necessary for professional development. They also offer opportunities to collaborate, develop professional relationships, present papers, and learn techniques and treatments.

In Massachusetts, Black physicians could join the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS), established in 1791. MMS accepted its first Black physician, John Van Surly DeGrasse, in 1854. Dr. DeGrasse’s papers are in the Degrasse-Howard Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Although state and local medical societies could choose to accept members of color, many did not. The American Medical Association (AMA) delegated membership decisions to the state level until the 1960s.

The AMA, founded in 1847 as a national medical association, was created amid a climate of racial tension and debate over the institution of slavery. The AMA did not overtly disallow physicians of color from becoming members, but incidents at the 1870 and 1872 national meetings led to a policy that effectively excluded African American members.

At the 1870 meeting of the AMA, the all-white Medical Society of the District of Columbia challenged the authenticity of the integrated Washington D.C. National Medical Society, claiming that it had been founded to undermine the Medical Society. The Washington D.C. National Medical Society maintained that it incorporated because the Medical Society of the District of Columbia would not accept physicians of color as members. During the meeting, the issue of two societies was debated, and the Washington D.C. National Medical Society members were excluded from membership in the AMA. John L. Sullivan, a physician from Massachusetts, proposed that the AMA adopt a policy of racial non-discrimination but his proposal was tabled after the meeting.

After another attempt to seat an integrated medical society delegation at the AMA’s 1872 national meeting, a policy was enacted in 1874 to change the structure of seating medical societies at the national convention. While in the past any medical society, school, or institution could send a delegation to the national convention, now state and local societies would determine which societies would be officially recognized by the AMA, and only one society was allowed to represent a given region. This policy excluded most African American members because many local societies practiced racial exclusion.

In response, several integrated medical societies were founded on a local level, including the Medico-Chirurgical Society of the District of Columbia, the Lone Star State Medical, Dental, and Pharmaceutical Association of Texas, the Old North State Medical Society of North Carolina, and the North Jersey National Medical Association.

After years of attempts by Black physicians around the United States to integrate the AMA, the National Association of Colored Physicians, Dentists, and Pharmacists was created in 1895 in Atlanta, Georgia. The Association changed its name to the National Medical Association (NMA) in 1903. In 1908, the NMA began to publish the Journal of the National Medical Association. The credo of the organization, as laid out by the journal’s first editor Dr. C.V. Roman, is:

“Conceived in no spirit of racial exclusiveness, fostering no ethnic antagonism, but born of the exigencies of the American environment, the National Medical Association has for its object the banding together for mutual cooperation and helpfulness, the men and women of African descent who are legally and honorably engaged in the practice of the cognate professions of medicine, surgery, pharmacy and dentistry.”

For more information on the history of the National Medical Association, see Dr. Karen Morris’s thesis The Founding of the National Medical Association.

For a timeline on African American Physicians and Organized Medicine from 1846-1968, visit: https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/ama-history/african-american-physicians-organized-medicine-timeline.pdf.

1896-1959: “Separate But Equal” to Brown v. Board of Education

Plessy v. Ferguson was an 1896 Supreme Court Case that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation laws for public facilities if those facilities were of equal quality. The court case was brought by Homer Plessy, a person of 1/8 Black heritage and resident of New Orleans who purposefully violated the city’s Separate Car Act of 1890. His suit argued that separate but equal accommodations for Black and White passengers was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court issued a 7-1 decision against Plessy.

In 1904, the American Medical Association created the Council on Medical Education to evaluate and restructure medical education. Abraham Flexner, an educator and reformer who published The American College: A Criticism in 1908, was hired to study American medical schools. The 1910 Flexner Report examined medical education and suggested reform for medical colleges, which included increasing standards, partnering with hospitals for clinical training, and closing schools that could not afford to update and maintain facilities. The Flexner Report drastically changed medical education, especially for African American physicians. Flexner recommended coeducation of men and women in medical schools, but believed that Black physicians should be trained to serve Black communities. Prior to the report, there were over 20 Black medical schools in the Unites States. Within a decade only two remained: Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., and Meharry Medical College in Nashville, TN.

For more information about the Flexner Report, see Abraham Flexner and the Black Medical Schools by Todd Savitt. The Flexner Report is available online through the Carnegie Foundation Archives.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded on February 12, 1909, by a group of activists including W.E.B. Du Bois (the first African-American to earn a doctorate at Harvard), Ida B. Wells, Archibald Grimke, Mary Church Terrell, Henry Moskowitz, Mary White Ovington, William English Walling, Florence Kelley, Oswald Garrison Villard, and Charles Edward Russell. The organization held its first conference on May 30, 1909, and at its second conference on May 30, 1910, members named the organization the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and elected its first officers. The organization was incorporated in 1911 with the mission:

To promote equality of rights and to eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the courts, education for their children, employment according to their ability and complete equality before law.

The Boston Branch was established at the 1911 meeting, and was the first branch of the organization.

Annie Elizabeth “Bessie” Delaney was born in 1891 in North Carolina. During World War I, she moved to New York with her younger sister, Sarah (or “Sadie”). Bessie was the only African-American woman entering the 1919 class at the Columbia School of Dental and Oral Surgery. She graduated in 1923, becoming the second African-American registered dentist in the state of New York. Commonly referred to as “Dr. Bessie,” she practiced dentistry in Harlem, where she was an important community member. Columbia's School of Dental and Oral Surgery awarded her the Distinguished Alumna Award for her trailblazing work as an African-American woman in the field of dentistry in 1994.

The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” began in 1932. The Public Health Service and the Tuskegee Institute partnered to study syphilis in hopes of justifying treatment programs for Black people. Participants in the study were unaware of the parameters of the study which was conducted without informed consent. The 600 men in the study, 399 already infected by syphilis, 201 without, were told they were being treated for “bad blood,” and were not given proper treatment to cure their illness.

The study went on for 40 years, and participants were still not given adequate treatment even after penicillin became the standard treatment for syphilis. In 1972, an Associated Press story broke, and the study was terminated. The Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention appointed an ad hoc advisory panel to review the study, finding that although the men agreed to certain terms of the experiment, they were not informed of the study’s actual purpose. A class action lawsuit was filed on behalf of study participants and their descendants, and the US government paid $10 million and agreed to provide free medical treatment to surviving participants and family members infected as a consequence of the study.

The study led to the establishment of the Office for Human Research Protections and federal regulations requiring institutional Review Boards for the protection of human subjects in studies.

On August 13, 1946, the Hill-Burton Act was signed into law by President Harry S. Truman. The bill, known formally as the Hospital Survey and Construction Act, was a Truman initiative that provided construction grants and loans to build hospitals where they were needed and would be sustainable. The Hill-Burton Act particularly impacted the South, where many of the facilities utilizing Hill-Burton funds were built, but the law codified the idea of “separate-but-equal” in hospitals. While outright discrimination against Black patients was not allowed, separate-but-equal facilities were built where Black and white patients were segregated by race.

After the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) spearheaded several lawsuits aimed to eliminate discrimination in hospitals, a federal court challenge overturned the “separate-but-equal” aspect of Hill-Burton in 1963. The act influenced hospital desegregation by denying funds to segregated institutions.

For more information on the Hill-Burton Act, see: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1448322/, The Hill-Burton Act and Civil Rights: Expanding Hospital Care for Black Southerners, 1939-1960 by Karen Kruse Thomas and https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/10/02/495775518/a-bygone-era-when-bipartisanship-led-to-health-care-transformation.

Executive Order 9981 abolished discrimination “on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin” in the United States Armed Forces. It was signed by President Harry S. Truman on July 26, 1948, and led to ending segregation in military schools, hospitals, and bases.

In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In 1951, a class action suit was filed against the Board of Education of the City of Topeka, Kansas, by thirteen Black parents on behalf of their twenty children after attempting to enroll the children in White-only public schools. The District Court ruled in favor of the Board of Education, citing Plessy v. Ferguson, before being heard before the Supreme Court.

1960-1978: The Civil Rights Movement and Upholding Affirmative Action

The Medical Committee for Civil Rights (MCCR) was founded in 1963 by Dr. Walter Lear to address racism in the American Medical Association (AMA). Dr. Lear led a demonstration of physicians at the 1963 AMA convention in Atlantic City, protesting their policies that did not require southern medical societies to integrate. This lack of policy enforcement denied hospital privileges to African-American physicians throughout the Deep South.

On August 28, 1963, the MCCR participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, represented by a coalition of more than 200 medical professionals. Due to a lack of funding, the MCCR closed later that year. The organization was succeeded by the Medical Committee on Human Rights in 1964, known as the medical arm of the civil rights movement of the 1960’s. MCHR provided medical support civil rights workers and volunteers during Freedom Summer, the march from Selma to Montgomery, and other demonstrations throughout the movement.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act is a landmark act that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It also prohibits unequal application of voter registration requirements, as well as racial segregation in schools, employment, or public accommodations.

Prior to 1965, hospitals in the U.S. were largely segregated. Medicare and Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act required the desegregation of hospitals in America. Non-compliance with the law would disqualify hospitals from receiving federal funding.

During the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson, the Department of Health Education and Welfare was charged with certifying non-discriminatory practices in hospitals. Federal inspectors and civil rights activists were sent to hospitals nationwide to inspect their compliance with the law and the hospitals’ eligibility to receive Medicare funds. David Barton Smith, professor emeritus of healthcare management at Temple University, authored the book, The Power to Heal: Civil Rights, Medicare, and the Struggle to Transform America's Health Care System. In an article in U.S. News and World Report, Smith summarized, “With the passage of Medicare, hospitals quickly integrated—a thousand in less than four months.”

Executive Order 11246 established requirements for non-discriminatory practices in hiring and employment by government contractors. The executive order was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson on September 24, 1965. It also required contractors to implement affirmative action plans to increase the participation of minorities and women in the workplace.

There are two amendments to Executive Order 11246: Executive Order 11375 added the category “sex” to anti-discrimination provisions, and Executive Order 13672 changed “sexual orientation” to “sexual orientation, gender identity.”

The Association of American Indian Physicians was founded in 1971 by a group of fourteen American Indian and Alaska Native physicians. The group wanted to establish an organization to provide support and services to American Indian and Alaska Native communities. The primary goal of the organization is to improve the health of American Indian and Alaska Natives. Adoniram (Don) Van Bowen, Harvard Medical School’s first American Indian graduate, Class of 1976, served as President of the organization from 1983 to 1984.

Title IX of the Education Amendments Act is a federal civil rights law that protects people from discrimination based on sex in education programs or activities that receive federal funding. To learn more about Title IX at Harvard University, visit: https://titleix.harvard.edu/about-us.

In 1974, Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts laid out a plan to bus students between predominantly White and Black neighborhoods in Boston. Massachusetts had enacted the 1965 Racial Imbalance Act, which required schools to desegregate or risk losing educational funding. Public schools in the city of Boston were found to be unbalanced, but the Boston School Committee, under the leadership of Louise Day Hicks, refused to develop a busing plan or support its implementation.

The 1974 plan bused children across the city of Boston to different schools to end segregation, based on the city’s racially divided neighborhoods.

Boston was in turmoil over the 1974 busing plan and tensions around race affected discussion and protest over education for many years.

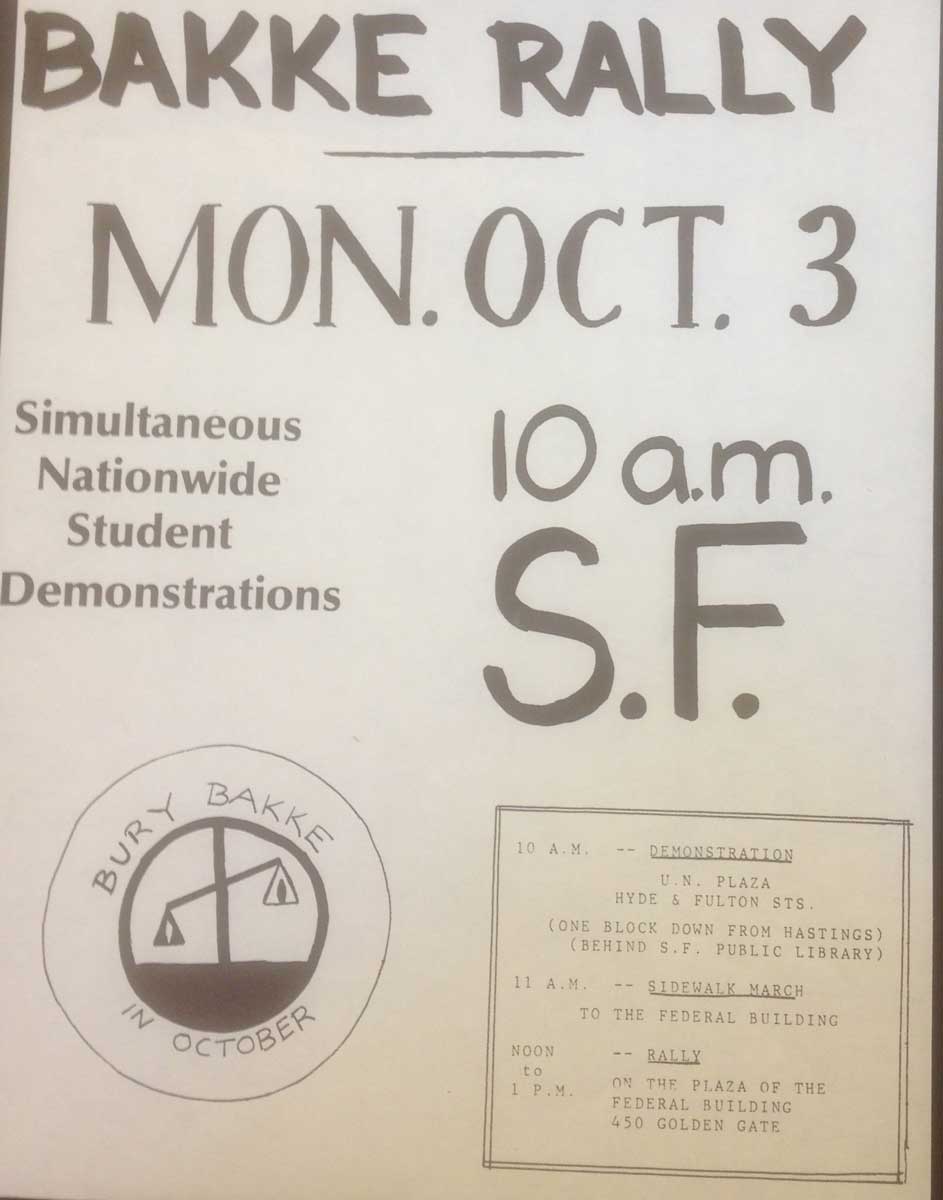

In 1978, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that race could be one of several factors in college admission policy, but that specific racial quotas were illegal. The case was brought to the Supreme Court after Allan P. Bakke sued the University of California, Davis. The school had rejected Bakke twice, and he challenged the constitutionality of the school’s affirmative action program. California's Supreme court ruled the program was a violation of white applicants’ rights, and ordered the school must admit Bakke. The U.S. Supreme Court accepted the case, and ultimately ruled in favor of affirmative action.

1979-today:

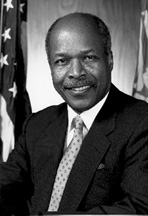

Louis Wade Sullivan was born in 1933 and grew up in rural Georgia. He matriculated at Morehouse College in Atlanta, GA, graduating in 1954 with a BS in premedical programs. Sullivan earned his medical degree from Boston University School of Medicine, entering as the only African-American in his class and graduating third in his class in 1958. Following medical school, Dr. Sullivan trained at New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center.

In the mid-1970s, Dr. Sullivan returned to Morehouse where he helped establish the Morehouse School of Medicine and was appointed founding dean. In 1989, under President George H.W. Bush, Dr. Louis W. Sullivan was appointed U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), making him the second African-American to serve in this role.

Patricia Roberts Harris was the first person and first African-American to serve as secretary of the newly reorganized Department of Health and Human Services in 1980.

After his tenure as Secretary of HHS, Dr. Sullivan returned to Morehouse School of Medicine to serve as two-time dean and president from 1993—2002.

Additionally, Dr. Sullivan was co-chair of the President’s Commission on HIV and AIDS (2001-2006), and chairman of the President’s Commission on Historically Black Colleges and Universities (2002—2009). Currently, he is the Chairman and Founder of the Sullivan Alliance to Transform the Health Professions, and President Emeritus of the Morehouse School of Medicine. For more information on Dr. Sullivan, read his memoir, Breaking Ground: My Life in Medicine (University of Georgia Press, 2014).

Antonio Coello Novello was born in Fajardo, Puerto Rico in 1944. She matriculated at the University of Puerto Rico from 1961–1965, earning a B.S. degree, and from 1965—1970, earning an MD degree. While in medical school, she met and married Joseph Novello, a US Navy doctor. Dr. Novello trained for her subspecialty in pediatric nephrology at the University of Michigan, where she was the first woman to be named Intern of the Year. She later attended Johns Hopkins University, graduating with a master’s degree in public health and a Doctor of Public Health degree in 1982 and 2000, respectively.

In 1990, Dr. Antonia Novello was appointed the 14th Surgeon General of the United States, making her the first woman and the first Hispanic person in the role. Sworn in by Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Conner, Dr. Novello served for three years.

The Americans with Disabilities Act is a civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against people with disabilities in all public and privates places that are open to the general public, and in all parts of public life, including employment, education, and transportation. To learn more about Harvard University’s Disability Resources, visit: https://accessibility.harvard.edu/.

Minnie Joycelyn Jones was born in Schaal, Arkansas in 1933 to sharecropper parents. She and her seven younger siblings often worked in the cotton fields, frequently missing school, primarily during harvest time, September to December. Joycelyn Jones entered Philander Smith College, an historically Black college in Little Rock, AR, at the age of 15 on a scholarship from United Methodist Church. Graduating in only three years, she joined the US Army and trained in physical therapy in Houston, TX. In 1956, she enrolled in the University of Arkansas Medical School on the GI Bill. Four years later, she was the only woman to graduate from the school, earning her medical degree. 1960 was also the year that she married Oliver Elders.

Dr. Joycelyn Elders completed her training and earned a master’s degree in biochemistry from the University of Arkansas in 1967. She joined the faculty of the University of Arkansas School of Medicine as a clinician and researcher in pediatric endocrinology.

In 1993, Dr. Joycelyn Elders was appointed the 15th Surgeon General of the US, becoming the first African-American and the second woman in the role. She was appointed by President Bill Clinton, who, as Governor, had appointed Dr. Elders as head of the Arkansas Department of Health from 1987-1992. Dr. Elders served as Surgeon General for 15 months, and in 1995 returned to the University of Arkansas as a faculty researcher and professor of pediatric endocrinology at Arkansas Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Elders wrote her autobiography (with David Chanoff) in 1996, entitled Joycelyn Elders, M.D.: From Sharecropper’s Daughter to Surgeon General of the United States of America. She is now Professor Emerita at the University of Arkansas School of Medicine. Her recent work includes advocating for more Black physicians in the medical field.

David Satcher was born in Anniston, Alabama in 1941. He matriculated at Morehouse College earning a BS, and then at Case Western Reserve University, earning his MD and PhD. In 1993, Dr. Satcher became the first African-American Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A physician-scientist and public health administrator, Dr. Satcher was a four-star admiral in the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. As the 16th Surgeon General of the United States, from 1998-2002, he was the first African-American to hold the position. Additionally, he was the 10th Secretary for Health in the Department of Health and Human Services from 1998-2001, the first African-American man serving in this role. He was only the second person in history to serve in these two positions concurrently.

During his career as a physician and professor, Dr. Satcher held top leadership positions at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Morehouse School of Medicine, and Meharry Medical College. In 2006, Dr. David Satcher founded the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, where he is the director and senior advisor.

The National Hispanic Medical Association (NHMA) was established in 1994 in Washington, DC. The organization was announced at a White House Press Conference in December 1993 with President Bill Clinton, First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, and ten medical association leaders. NHMA’s founders were physicians who attended the White House Health Care Reform Task Force meetings in 1993 and 1994, advocating for Hispanic health issues.

Today, the organization represents the interests of 50,000 Hispanic physicians in the United States. To learn more, visit: http://www.nhmamd.org/about/about-nhma/.

Richard H. Carmona was born in 1949 and raised in New York City. He dropped out of high school and enlisted in the US Army in 1967, where he earned his General Equivalency Diploma. Through his service with the US Army Special Forces in Vietnam, Carmona became a decorated combat veteran. After leaving active duty, Richard Carmona attended Bronx Community College through an open enrollment program for veterans and received his associate of arts degree. His education continued at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), where he earned a Bachelor of Science degree and medical doctor degree in 1977 and 1979, respectively. He was awarded the prestigious Gold-Headed Cane as the top graduate of UCSF Medical School. He completed his subspecialty training in general and vascular surgery and went on to earn a master’s degree in public health from the University of Arizona in 1998.

In 2002, Dr. Richard H. Carmona was appointed by President George W. Bush as the 17th Surgeon General of the United States, making him the first Hispanic man to serve in this capacity. Dr. Carmona left the office in 2006 after completing his four-year term. Currently, Dr. Carmona is the Distinguished Professor of Public Health, Health Promotion Sciences and Community, Environment and Policy (ESHS) at the University of Arizona Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health.

Grutter v. Bollinger was a landmark case of the Supreme Court concerning affirmative action in student admissions. A prospective student to the University of Michigan Law School, Barbara Grutter, alleged that she was discriminated against on the basis of race after she was denied admission to the school. Grutter argued that she was rejected because the Law School used race as a predominant factor, giving some minority applicants a greater chance of admission than students with similar credentials from majority groups. The defendant of the case was President of the University of Michigan, Lee Bollinger.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court upheld that an admissions process that favors underrepresented minority applicants does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause so long as the process also takes into account other credentials on an individual basis for every applicant.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) are the first part of the comprehensive healthcare reform law signed by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010. The ACA, colloquially referred to as “Obamacare,” extended insurance coverage to millions of previously uninsured Americans, outlined measures to lower healthcare costs and bolster efficiency and innovation in health-related research, and banned harmful insurance practices, including rescission and denial of coverage due to pre-existing conditions.

The second part, the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act, was signed on March 30, 2010. The law provides rights and protections that make health coverage fairer and easier to understand, along with subsidies to make it more affordable. The law, the most significant regulatory overhaul of health insurance coverage since the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, also expanded the Medicaid program to cover more people with low incomes. The healthcare law is sometimes known as “Obamacare.”

Fisher v. University of Texas is a Supreme Court case concerning the affirmative action policy of the University of Texas at Austin. The suit, initially brought by Abigail Fisher and Rachel Michalewicz in 2008, alleged that the University of Texas at Austin discriminated against both women on the basis of their race in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Michalewicz withdrew from the case in 2011.

The original Supreme Court hearing of the case took place between 2011 and 2013, and in 2014, ruled in favor of University of Texas at Austin to use race as part of a holistic admissions program. In 2015, Fisher again challenged University of Texas at Austin’s admissions policy, and in 2016, the Supreme Court upheld that the race-conscious admissions program is legal under the Equal Protection Clause.

In 2014, Harvard College was sued by the group Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), founded by Edward Blum, an anti-affirmative action activist. Blum and SFFA have a history of litigation targeting civil rights protections. The lawsuit alleged that Harvard College discriminated against Asian-American applicants based on their race.

In 2019, Federal Judge Allison D. Burroughs ruled in favor of Harvard, upholding Harvard’s admissions policy and ruling that the University’s admissions policy does not discriminate on the basis of race, does not use racial quotas, and does not over-emphasize race when considering an applicant’s admissions file.

In a letter to the Harvard community following the ruling, President Larry Bacow wrote:

“The consideration of race, alongside many other factors, helps us achieve our goal of creating a diverse student body that enriches the education of every student. Everyone admitted to Harvard College has something unique to offer our community, and today we reaffirm the importance of diversity — and everything it represents to the world.”

The COVID-19 virus was first documented in Wuhan, China, and spread to the United States in February 2020. A national emergency was declared on March 13, 2020, and ended on April 10, 2023. Harvard University shifted classes online in response to rising COVID-19 cases during the spring of 2020. Hybrid teaching began in the Fall 2021 semester, offering both in-person and online classes. The pandemic greatly affected hospitals across the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected Black, Latino, and American Indian/Alaskan Native communities. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) reported in 2021 that COVID-19 had caused more deaths by population size in Black, Latino, and American Indian/Alaskan Native people than in white or Asian people. Such inequities emerged in the context of multiple social forces, such as pre-existing co-morbidities related to socioeconomic status and structural racism.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, over one million Americans have died of the virus as of January 2024.

Learn more about how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the Black community at The Black Frontline, an oral history project where Black healthcare workers share their stories from working on the frontlines.

Xenophobic and racist rhetoric and incidents targeted at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) increased dramatically during the pandemic, leading to the creation of the Stop AAPI Hate movement and an organization by the same name. The hashtag #StopAAPIHate trended on social media platforms as people advocated for an end to targeted racial hate crimes.

Stop AAPI Hate defines itself and its mission as “a US-based coalition dedicated to ending racism and discrimination against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAs & PIs). We strive to advance the multiracial movement for equity and justice by building power for our communities, working in solidarity with other communities of color, and advocating for comprehensive solutions that tackle the root causes of race-based hate.”

On May 25, 2020, a video depicting an incident of police brutality in Minneapolis, MN was posted to social media sites and quickly went viral. The video showed the murder of George Floyd, a 46-year-old African-American man, by a white police officer.

Floyd’s death sparked a wave of national and international protests against police brutality and structural racism more generally. The Black Lives Matter movement has been at the forefront of the fight for racial justice for Black people since the early 2010s; it had another resurgence following George Floyd’s death. Its corresponding hashtag, #BlackLivesMatter, trended on social media sites. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuing quarantine and social distancing guidelines, the hashtag became a hub of activism where people organized protests, spread resources, and expressed their emotions about what had transpired. The protests held after Floyd’s death were the largest in the country since the Civil Rights era. Protestors rallied around Floyd’s words, “I can’t breathe.”

Leading political science scholar Dr. Claudine Gay assumed office as the 30th President of Harvard University in 2023, making her the university’s first Black president since its founding in 1636 and the second woman president. Dr. Gay earned her PhD in political science from Harvard University in 1998. She returned to Harvard in 2006 as a professor of government and became professor of African-American studies a year later. She was named both dean of Social Studies at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and the Wilbur A. Cowett Professor of Government and African and African-American Studies in 2015. Three years later, she became the Edgerley Family Dean of the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Dr. Gay served from September 2023 until her resignation in January 2024.

In June 2023, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that Harvard College and the University of North Carolina’s admissions programs violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, which prohibits race-based discrimination by the government. Harvard’s nine-year effort to defend its policies came to a close, and the ruling effectively ended race-conscious affirmative action in the admissions programs of public and private universities.

Former Harvard University President Larry Bacow wrote in a letter responding to the ruling: “To prepare leaders for a complex world, Harvard must admit and educate a student body whose members reflect and have lived, multiple facets of human experience. No part of what makes us who we are could ever be irrelevant. Harvard must always be a place of opportunity, a place whose doors remain open to those to whom they had long been closed, a place where many will have the chance to live dreams their parents or grandparents could not have dreamed.”