Interviews

Harvard Medical

School History

1920—1967

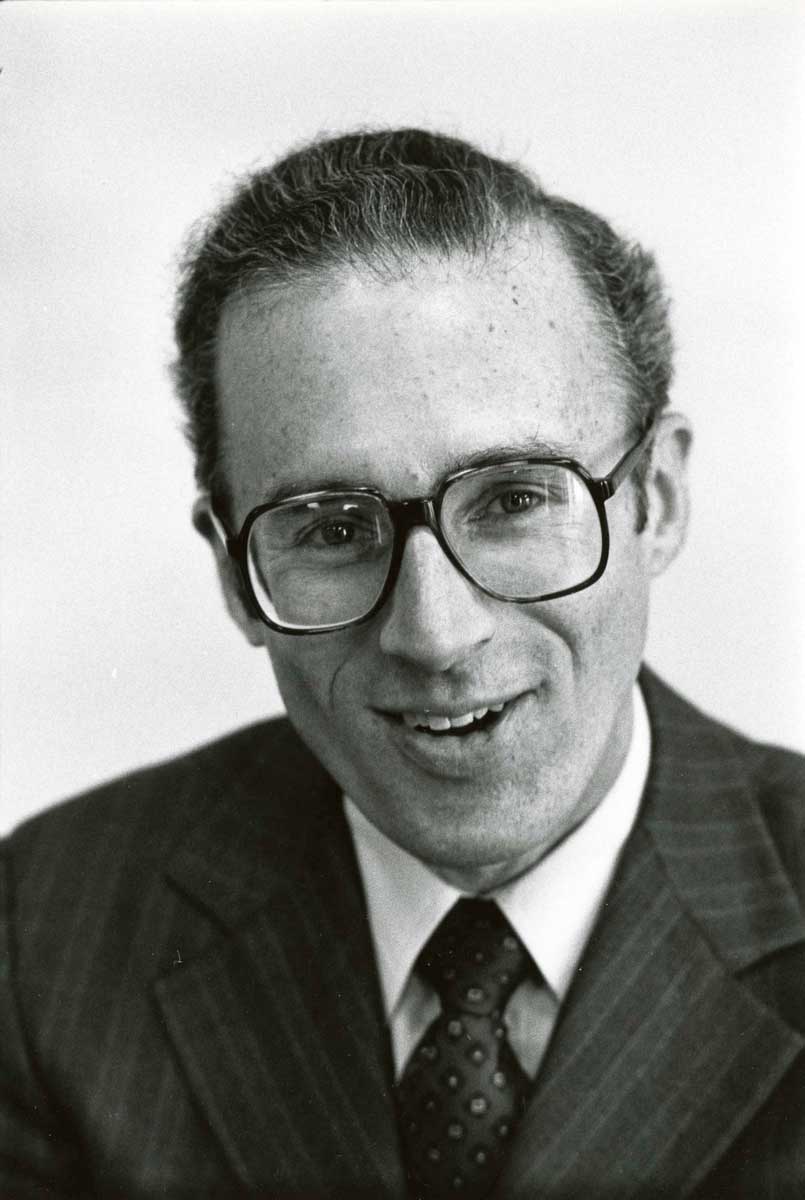

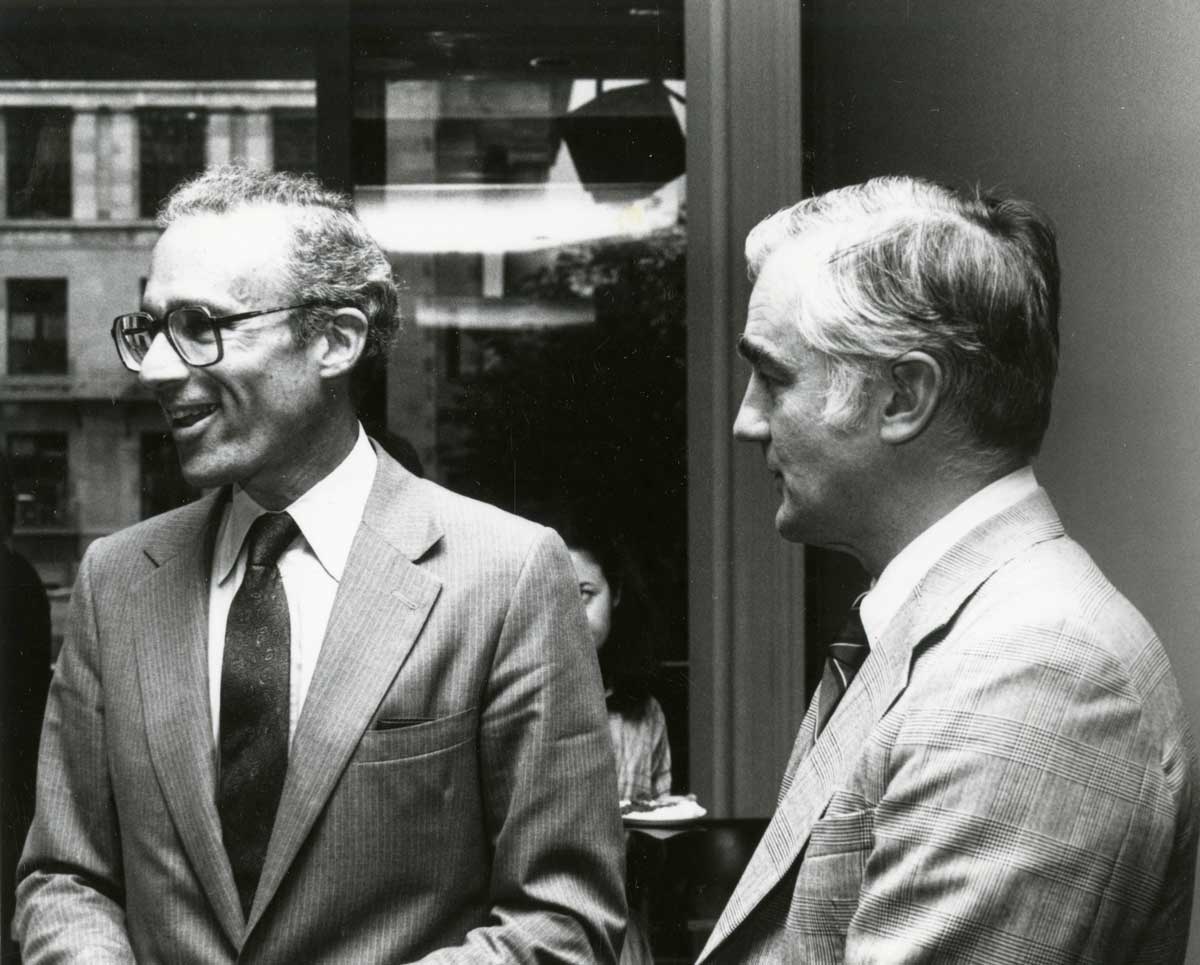

Professor of Medicine

Dean of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 1972-1984

Howard H. Hiatt, MD, was born in Patchogue, NY. He enrolled in Harvard College in 1944 and ascended to Harvard Medical School (graduating in 1948) without first earning his AB degree.

Dr. Hiatt was the first Blumgart Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and the physician-in-chief at Beth Israel Hospital from 1963 to 1972. In 1972, he became the dean of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, a role he held until 1984.

In 1985, he resumed teaching at Harvard Medical School and as a Senior Physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital. He is a member of the Board of Directors of Partners in Health and a member emeritus of the Task Force for Global Health. Dr. Hiatt is a leader in the field of human rights.

”…… when we started the program at Beth Israel Hospital -- the training program -- there were no women in the residency -- or almost none. We started something in that realm. There were no minorities in the residency -- we addressed that problem too. And, that, you know, was an opportunity I had to address issues that I thought needed attention.” (1:10-1:38)

“I became conscious of how much the Beth Israel Hospital was doing for the patients who came to it, but how little we were doing for people not very far away, who lived in impoverished areas in Boston. That was a lesson that was not difficult to learn.” (13:44-14:10)

“Because the war was on and it was really not possible to continue without abbreviating considerably my college experience, I left without a Harvard degree, that is, a bachelor’s degree.” (27:56-28:39)

“And we began -- we continued to do what I’d been doing. Continued to work in neighborhoods. I had tried -- started -- some programs. Many. And tried to start others. For example, I wanted to change the principal degree at the School of Public Health is what’s called the MPH, the Masters of Public Health.” (38:50-39:28)

“It’s now the biggest program in the School of Public Health. It, I think, takes 170 students a year for a two-year program. The only reason it’s not more than 170 is that there’s no amphitheater over there that takes more. It’s the biggest program at the school and it’s the program I wanted to set up at the school and now exists at the school.” (43:46-44:19)

“So, that was the beginning of the Division of Global Health Equity…that’s been my activity here, primarily, and now helping that get underway is establishing a relationship with the 501(c)(3) organization called Partners in Health.” (47:07-47:44)

”And then I had a call from the new president of Yale. He said that he had heard about my interests. He said he thought they coincided with his, and would I come to New Haven and look at that position? I did, and it looked just right. He was all for bringing the medical school and the university together in closer relationship and for bringing the medical school into closer relationship with its community.” (53:36-54:17)

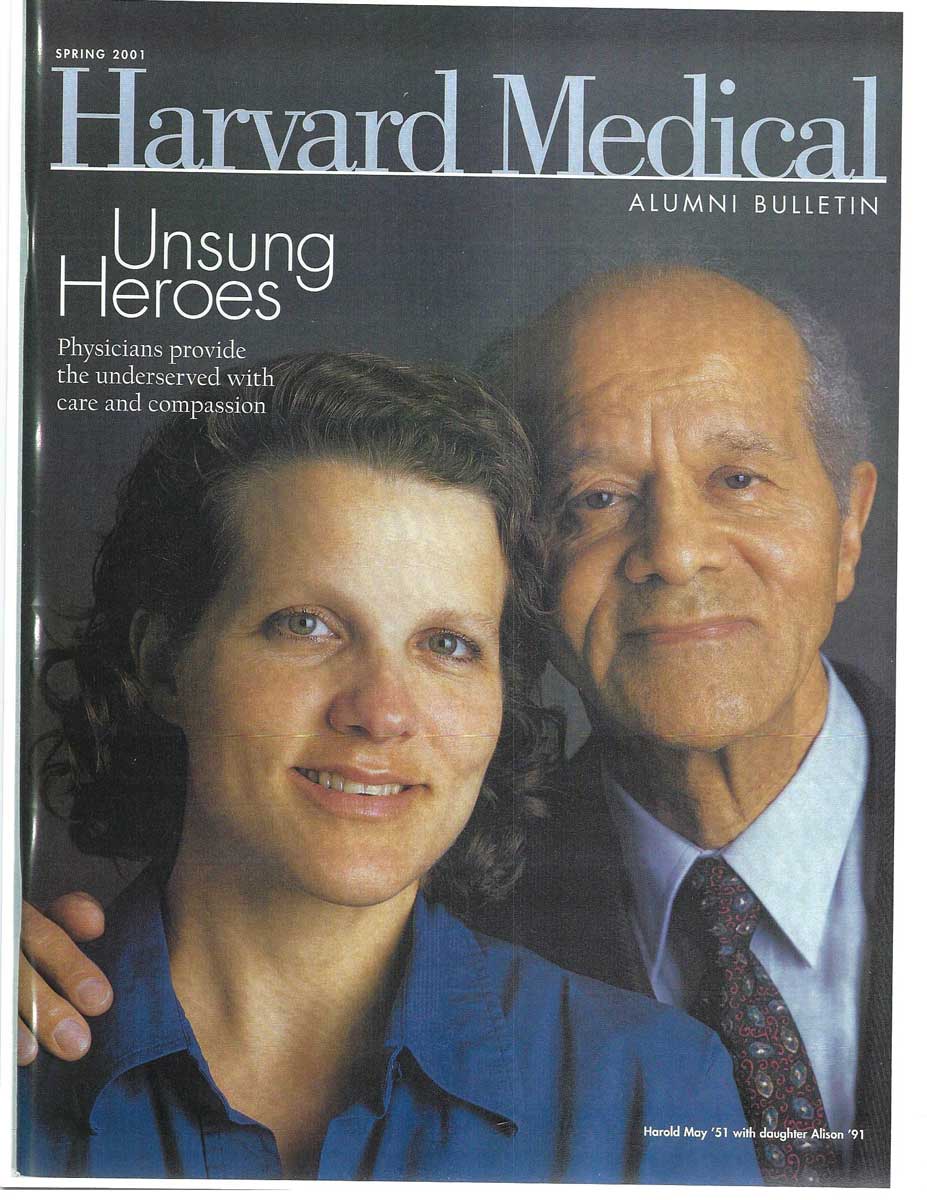

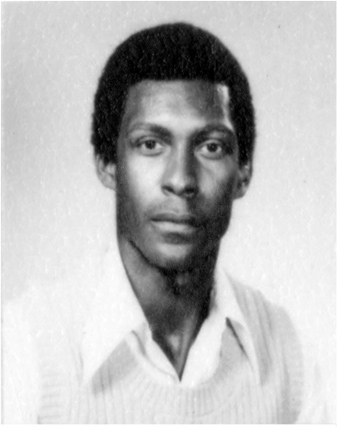

Matriculated 1947; Graduated Class of 1951

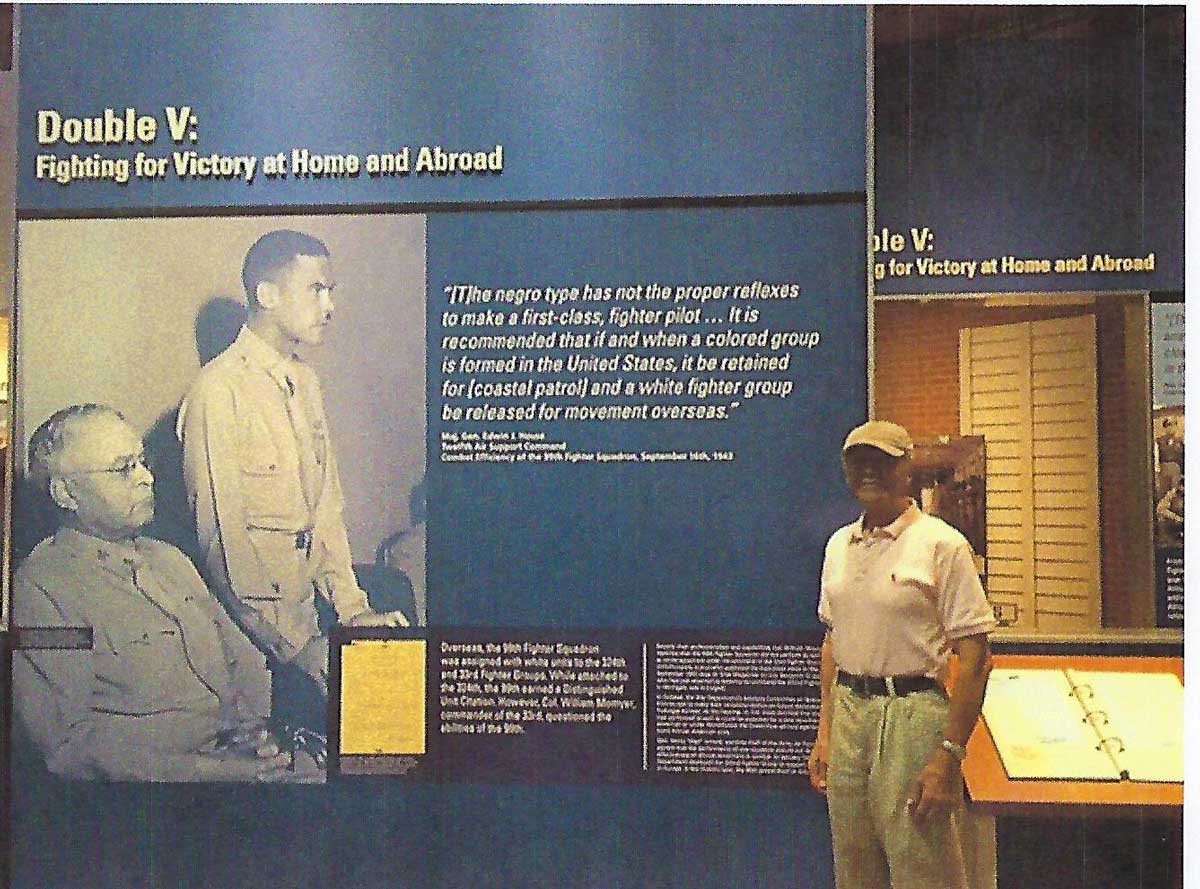

Harold May was born in Peekskill, NY, in 1926. He entered Harvard College in 1944 as part of the accelerated program during World War II and entered the Air Corps in 1945, becoming part of the Tuskegee Airmen program. After the war, Dr. May returned to Harvard, and entered Harvard Medical School in 1947.

After medical school, Dr. May completed a surgical residency at Massachusetts General Hospital, which was interrupted by eye surgery. During his convalescence, he traveled to Haiti and, after his residency, returned to Haiti, where he worked at the Albert Schweitzer Hospital. He also served as Director of Community Health at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Medical Director of the Wrentham Developmental Center, and as Founder of FAMILY, Inc., a non-profit which creates secure and nurturing environments of mutual supports in which all children and families can thrive.

"And so all of these factors just entered into who I am and who I have been in my life ever since."

"But December 7th, 1941 was a turning point for my life and the life of every boy in our nation because we knew that we were going to be at war."

"We were going to Tuskegee because of segregation, overt segregation."

"I went to Dr. Churchill and said, 'Dr. Churchill, I want to give my resignation because I’m going to have to leave the residency because I can’t see.'"

"And I couldn’t shake that image that what Haiti needs, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, what Haiti needs is Tuskegee. It needs development. And so education is critical."

"And I wondered what is my role here. Here I am. I knew I needed to be in Haiti. And I was expecting to be there for the rest of my life. I was fully expecting that. But in the back of my mind I had this nagging concern, how about our own -- how about the United States."

"So it seems that I would be a strange person to pick to take leadership of the division of community health or -- they called it community medicine. Me, with my experience in Haiti, just this beautiful but very very poor country which is rural. And here I was in urban America. But that’s what the challenge was."

"I love America. I love America and I praise God that I was born here. That’s a blessing. But I think the light has to start shining here. There has to be a light. There has to be a beacon that says, 'Look, this is the way.' And this is the way, the fact is we’re one family."

Photographs courtesy of Harold May.

Graduated Harvard College 1948, Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1952

Chester Middlebrook Pierce (1927-2016), was an emeritus professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and an emeritus professor of education at the Harvard School of Education. He was the first African- American full professor at Massachusetts General Hospital and practiced in the Department of Psychiatry for over 25 years. Dr. Pierce was also the past president of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and the American Orthopsychiatric Association, and was the founding president of the Black Psychiatrists of America. In 1970, Dr. Pierce was the first to use the term “microaggression” to describe insults and dismissals he regularly witnessed non-Black Americans inflict on African-Americans. Dr. Pierce was also a consultant for Sesame Street.

“Well, it was a time of, you know, a lot of social ferment around issues of race. And people were organizing and talking in all sorts of ways. And so it was not unusual for a group to get together, like… black psychiatrists.”

“Lots of places I know wouldn’t have given me the latitude to pursue things I wanted to pursue, and did, such as, you know, spending lots of time in Antarctica… But Harvard is indulgent.”

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1954

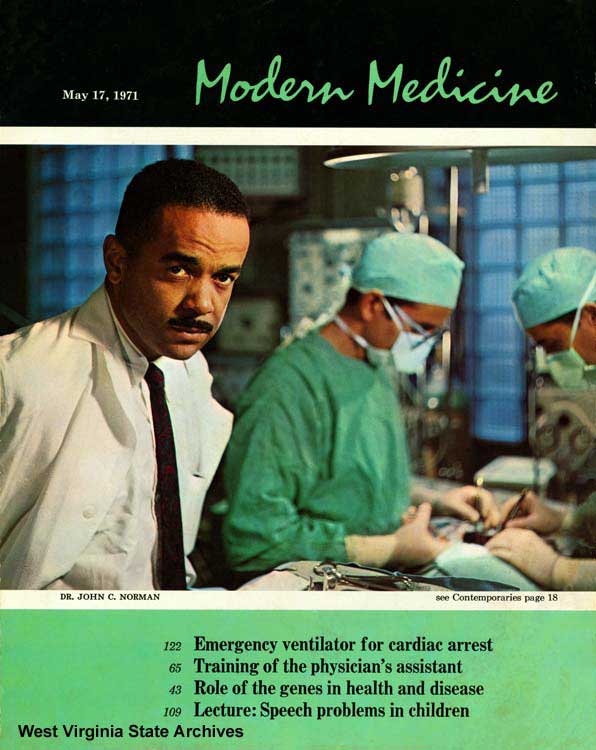

John C. Norman, MD (1930-2014), was born on May 11, 1930, in Charleston, WV. He entered Howard University at age 16 and transferred to Harvard College, where he graduated magna cum laude in 1950. Dr. Norman completed his medical degree in 1954. Following an internship and residency at Presbyterian Medical Center and Bellevue Hospital in New York, he joined the U.S. Navy, obtaining the rank of lieutenant commander. He completed his cardiac surgical training at the University of Michigan and, in 1962, was a National Institutes of Health fellow at the University of Birmingham, England.

Dr. Norman became an associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and undertook research projects involving organ transplantation. This work led him to the Texas Heart Institute in 1972, where he worked on developing the first abdominal left ventricular assist device. He later worked at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center in New Jersey and then as chairman of the surgery department at Marshall University School of Medicine.

Dr. Norman also organized the 1969 paper "Medicine in the Ghetto" that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine that same year.

His papers are available through the West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Dr. Norman's full oral history is available to researchers at the Center for the History of Medicine. Contact chm@hms.harvard.edu for more information.

"Being a student, I always said, regardless of where you are, or from whom you are, you could come to Harvard College or Harvard Medical School for that matter, and find someone of similar background, and form a solidarity, and that your standards would be raised forever, as they are today."

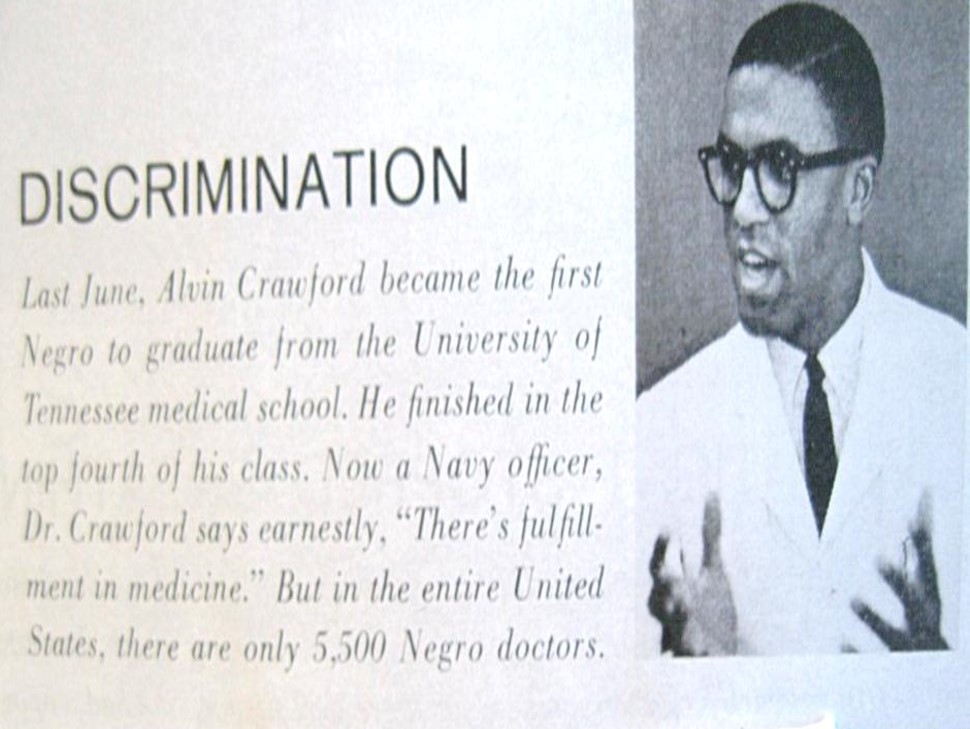

Alvin Crawford, MD, FACS, graduated cum laude from Tennessee State University in 1960, earning degrees in chemistry and music. In 1964, he became the first African-American to graduate from the University of Tennessee College of Medicine.

Dr. Crawford completed his residency at the U.S. Naval Hospital Chelsea (Boston), and the Combined Harvard Orthopaedic Residency Program at Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Crawford became the Director of Orthopaedic Surgery at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center in 1977 and remained chief for 29 years. He is one of the nation's foremost authorities on video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, and among his achievements is serving as the first African-American president of the Scoliosis Society.

“Well, you know, we think that you’ve got all it takes for the military, but I think that you could be better served, and we would like to have you trained at Harvard.” (8:18-8:27)

“But being as competitive as I am, I said, ‘Fine, and let’s start.’ So anyway, I went to school. I started at the University of Tennessee, in January of 1961.” (14:48-15:02)

“But so, Jack said, ‘Dr. Pampas, I have to tell you that Alvin is -- is -- he’s a Negro.’ I don’t recall exactly whether I was a ‘Negro’ or a ‘Black.’ I knew it wasn’t African American. That didn’t come until a long time after that. But anyway, Art just looked at him and said, ‘Well, do you think he could make it at 7:30?’ |LS|Laughter] And that was the end of it. And from that point on, things were good.” (20:22-20:48)

“And then I fell in love with orthopedists, because they weren’t saving anyone from death, but they were making everybody better. And I just loved it.” (26:34-26:48)

“Well, I went to Children’s |LS|Boston Children’s Hospital], and I fell in love with children. And the thing was that children want to get better and go out and play with their friends. And they don’t really care what you look like, or who you are, or whatever, so long as you can get them back to playing with their friends. And they love you forever.” (26:59-27:18)

“You have no idea as to how it feels to an organization of African-Americans |LS|that] people are talking about something…you are under the impression that you participated in. But there’s no documentation of it.” (50:18-50:39)

“But more important are what I consider, and I call euphemistically, my children. I had 57 fellows that I’ve trained, pretty much from all over the world. And a lot of them from under-developed, under-served countries, and I’ve not only trained them, they -- some have gone back from the States, and have done mission surgery in a lot of those places where they’ve been.” (38:27-38:52)

1968—1982

George Packer Berry Professor of Neurobiology

Edward Kravitz was born in 1932 in New York City, NY. He grew up in the Bronx and attended the City College of New York. He earned his PhD in biological chemistry at the University of Michigan, and was recruited to Harvard Medical School by Steve Kuffler in 1960.

Dr. Kravitz was part of the inaugural Neurobiology Department at Harvard Medical School, and in addition to his research on GABA, neurotransmitters, and neuroethology, he has been an advocate for diversity and inclusion throughout his career.

Interview Transcript

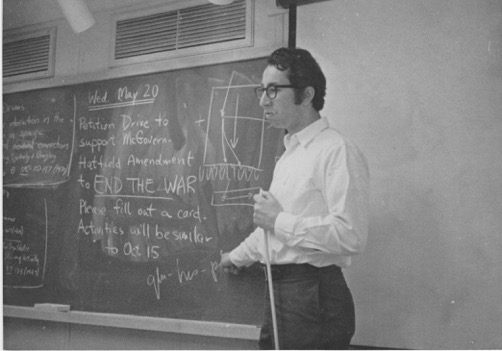

"And what changed that was what was happening in the country. Two things happened in the 1960s that dominated the news every night and eventually dominated our lives, even though we were mainly at Harvard, faculty members, to teach and do research. And one was the Vietnam War. And the other was the start of what eventually became the civil rights movement." (21:15)

”The thing that tipped the balance was the Martin Luther King assassination. And that just... It was April 1968, April 4th, 1968.” (25:00)

”That surprised us, that the dean of Harvard Medical School could not take a public stand on something that we thought was so important to Harvard Medical School. In any event, Bob Ebert told us how to do that. The faculty meeting was three weeks away. And he said, “At the next faculty meeting, you have to get the support of every clinical and preclinical chairman at Harvard Medical School.” Well, I should say, when he said that, our hearts sank a little bit.” (29:03)

”We were the second item on the -- on the meeting. And we had put it together by having a very conservative group of faculty present our case -- who supported us. John Beckwith read the document that we had written out and gave a few reasons for why we put down 15 students, as roughly 10% of the class, as a targeted goal, not as a quota.” (34:13)

”Bob Ebert, with a big smile, came over to us and said, “What’s wrong with you guys?” He said, “Don’t you know you’ve won?” And we said, “What do you mean won? We lost! We didn’t get the vote! We didn’t get the number.”” (38:40)

”1929 to 1969, 40-year period, there were 30 minority graduates of Harvard Medical School. In the 40 years after that period of time, there have been 1,000 graduates. So we didn’t change the country. We didn’t change the world. But we did change Harvard Medical School. And by changing Harvard Medical School, we changed American medicine.” (40:00)

”If there’s a message that I want to send to young people by this story, it’s get involved. … It’s not an either-or situation. You can have a wonderful career. You can become a scientist, a doctor, a lawyer, whatever you want to become. But there are injustices. There are things that we’re fighting about now that we thought the fights had been decided 50 years ago.” (52:15)

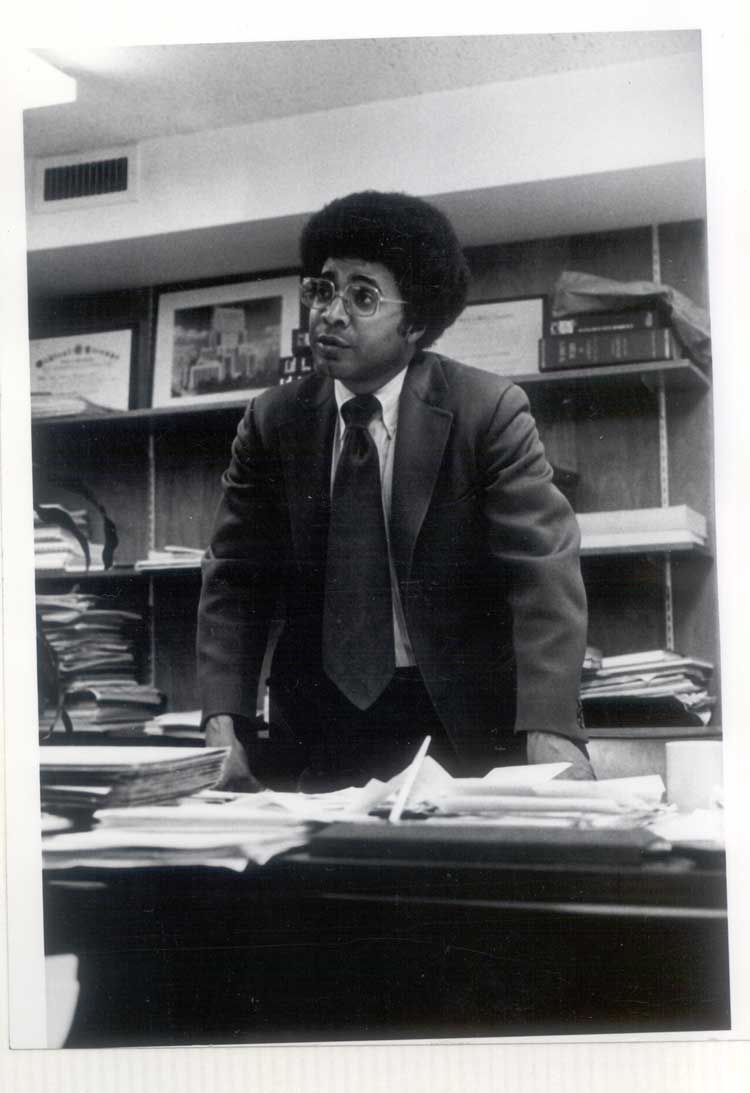

Professor of Psychiatry, Emeritus

Alvin Francis Poussaint, MD, was born in New York City, NY, in 1934. He attended Stuyvesant High School and Columbia University. He graduated from Columbia in 1956 with a bachelor's degree in pharmacology. He enrolled in Cornell Medical School and earned his medical degree in 1960. He became the Chief Resident at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute in 1964, but left the position to become the Southern Field Director of the Medical Committee for Human Rights in Jackson, MS in 1965. Dr. Poussaint also participated in the march from Selma to Montgomery to ensure that demonstrators would have medical care if needed.

In 1967, after leaving Mississippi, Dr. Poussaint joined the Tufts Medical School Faculty and, in 1969, joined Harvard Medical School as Associate Dean of Student Affairs. From 1975 to 1978, he was the Dean of Students at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Poussaint served as Faculty Associate Dean for Student Affairs at Harvard Medical School until his retirement in 2019 and was the founding Director of the Office of Recruitment & Multicultural Affairs in 1969.

Dr. Poussaint's oral history interview is closed to researchers until 2025. Please contact chm@hms.harvard.edu for more information.

Former Robert Henry Pfeiffer Professor of Neurobiology, Emeritus

Edwin Furshpan (1928 - 2019) completed his doctoral work at the California Institute of Technology in 1955. He worked in Bernard Katz’s laboratory in London, where he met David Potter. The two went on to work with Steve Kuffler at Johns Hopkins University.

Dr. Furshpan was part of the inaugural Neurobiology Department at Harvard Medical School in 1966. Throughout his career, he was an advocate for diversity and inclusion. Along with Dr. Potter, he founded the Native American High School Summer Program at Harvard Medical School to increase the number of Native American students attending leading colleges and universities.

"So we have this meeting, a stormy meeting, and the proposal, as you know, before the meeting, was that Harvard Medical School should undertake, should commit itself, to admitting a substantial number of, as the word was then, disadvantaged students. No mention of race, but disadvantaged."

“King was focused on something really important and went about it in the most productive and creative way. He managed to do it while insisting on nonviolence.”

”So we paid attention not only to grades. You know, grades were important, but if we thought somebody could do the work, we didn’t care whether they had all A’s, or whether they had 800s on their MCATs. It was character. It was accomplishment. It was motivation. It was vision.”

”You have to take into account not only where people are now, but where they came from.”

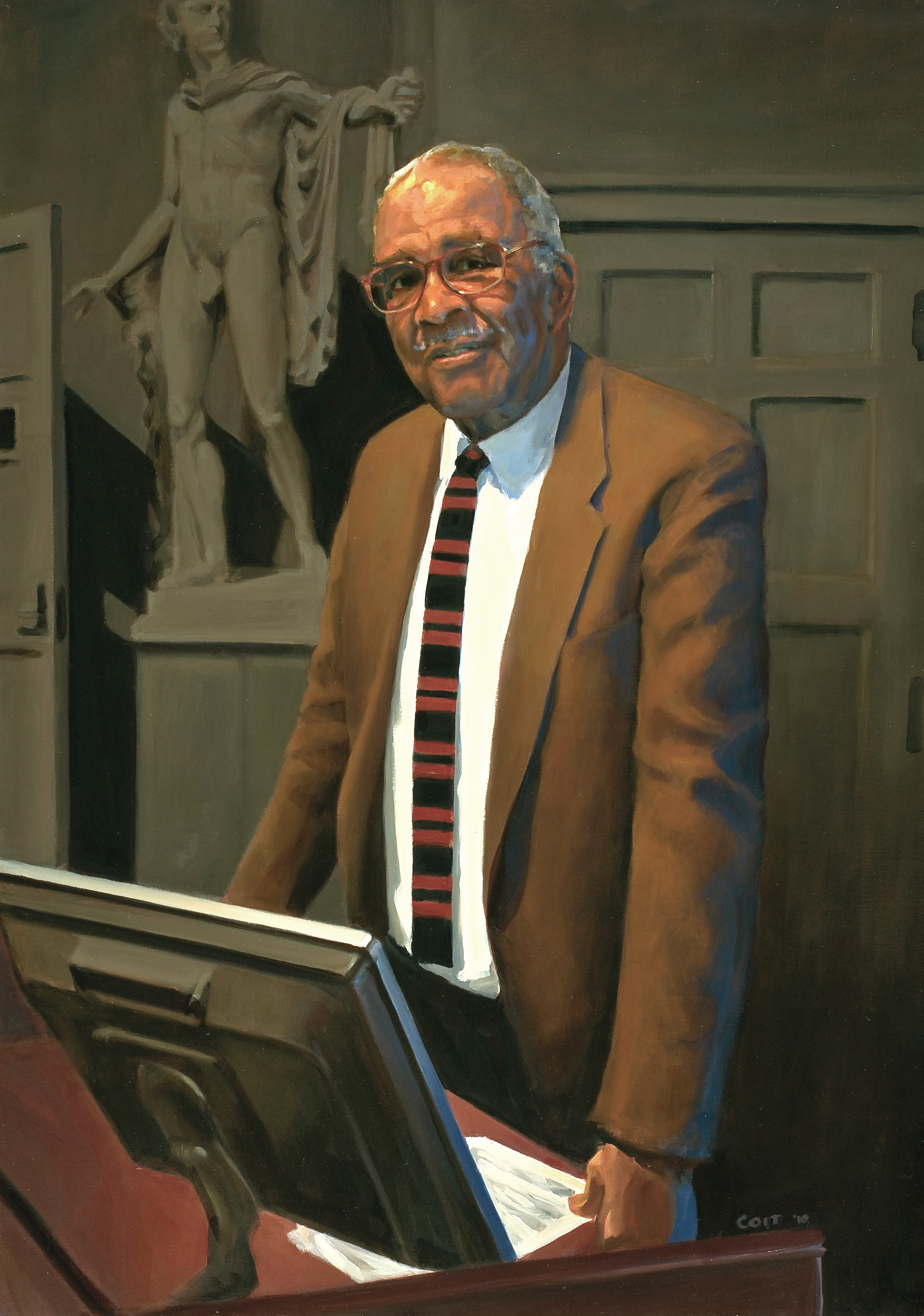

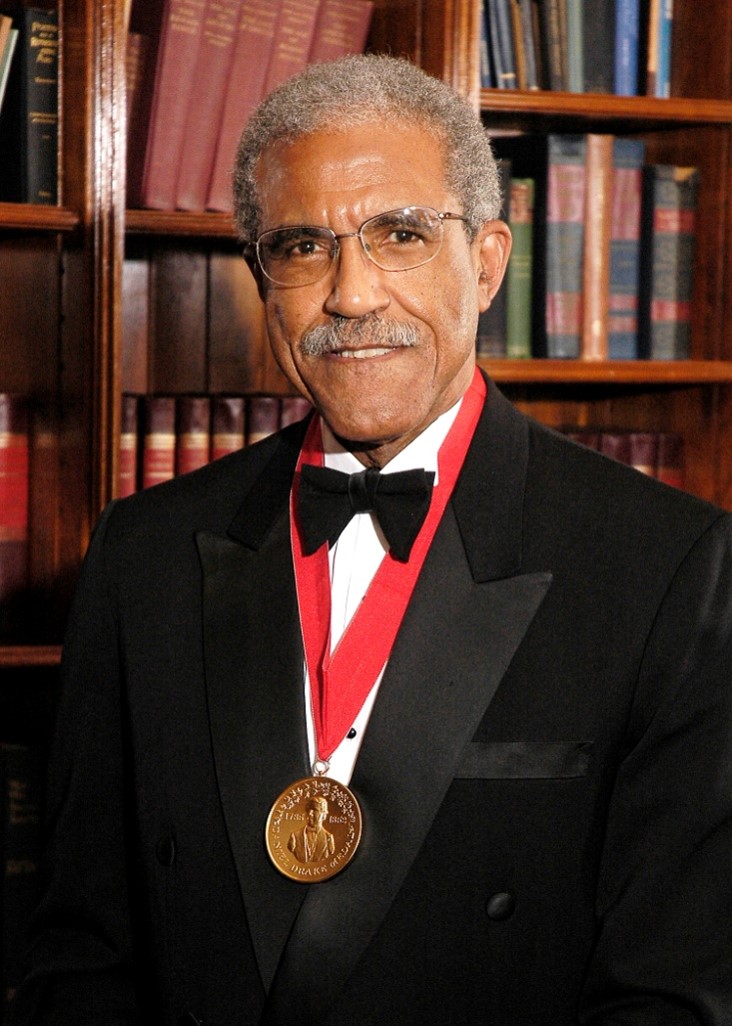

Augustus A. White III was born in Memphis, TN, in 1936. He attended segregated schools in Memphis, and graduated from the private Mount Herman School in Northfield, MA, in 1953. He completed his premedical studies at Brown University in Providence, RI.

Dr. White was the first African- American medical student at Stanford University, surgical resident at Yale University, professor of medicine at Yale, and department head at a Harvard-affiliated hospital (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center). From 1966 to 1968, he served as Captain in the United States Army Medical Corps and as a combat surgeon at the 85th Evacuation Hospital in Qui Nhon, Vietnam, from 1966 to 1967. Since retiring from surgery in 2001, Dr. White has researched and written about issues of diversity and cultural sensitivity in medicine.

Dr. Augustus White is the Ellen and Melvin Gordon Distinguished Professor of Medical Education at Harvard Medical School.

"People were of course aware and it would come up from time to time in conversation that I was the first African-American clinical chief or professor in surgery, you know, orthopedic surgery, but working in a hospital in that capacity..."

“And I went on to spend a year and a half in Sweden. And during that period I was working full time in research with no clinical responsibilities and able to complete a thesis and a doctoral thesis on the biomechanics of the spine, of the thoracic spine.”

”The year that I was accepted for the Ten Outstanding Men there were four African-Americans out of the 10 and it was pretty rare...The four individuals were Gale Sayers, who was a superstar professional running back, a fellow named Melvin Floyd who was a policeman and a minister and that was unique, and Jesse Jackson -- not Jesse Jackson Junior, Jesse Jackson -- and I was the fourth one.”

Graduate of the Harvard Medical School Dermatology Training Program, 1972

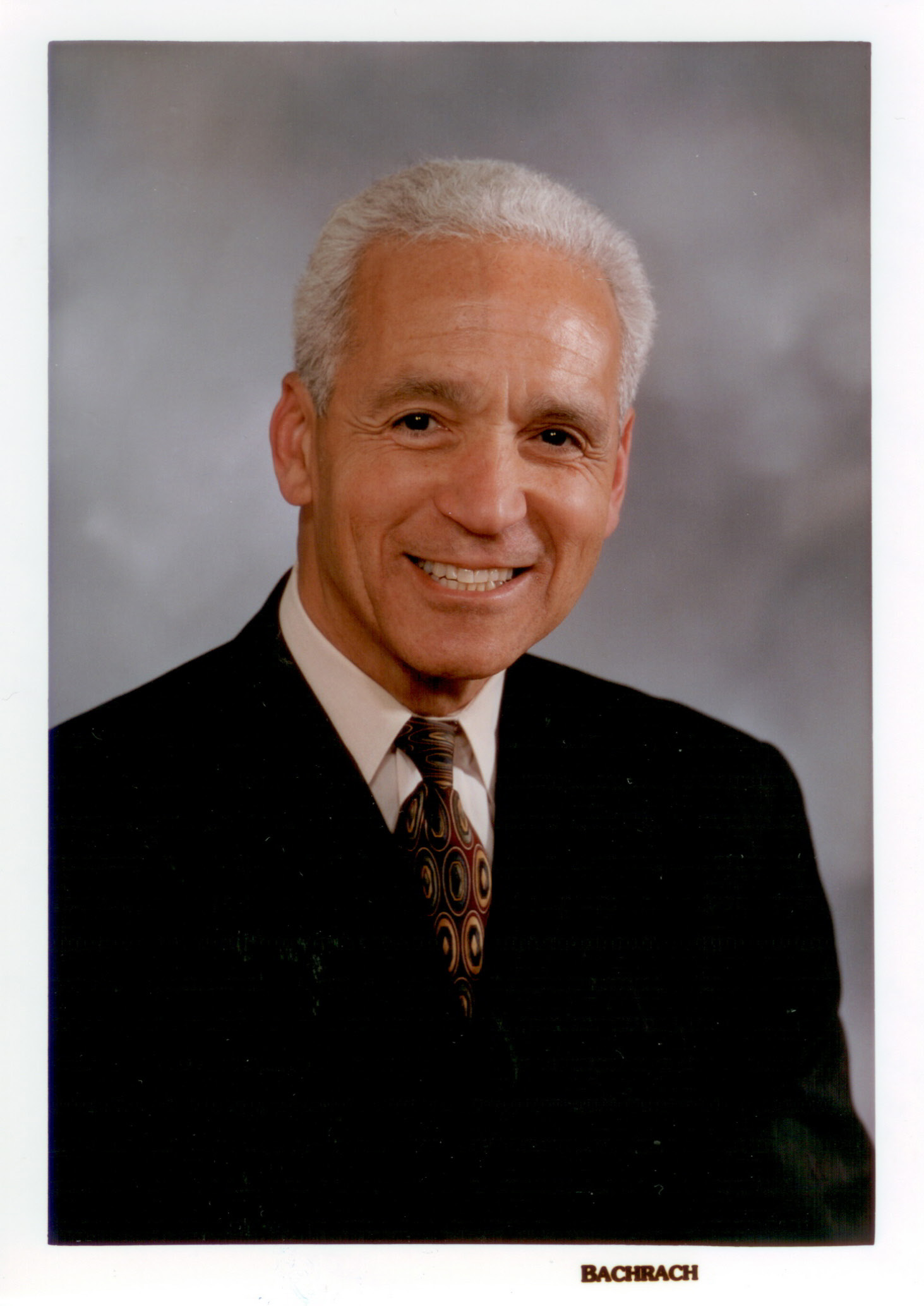

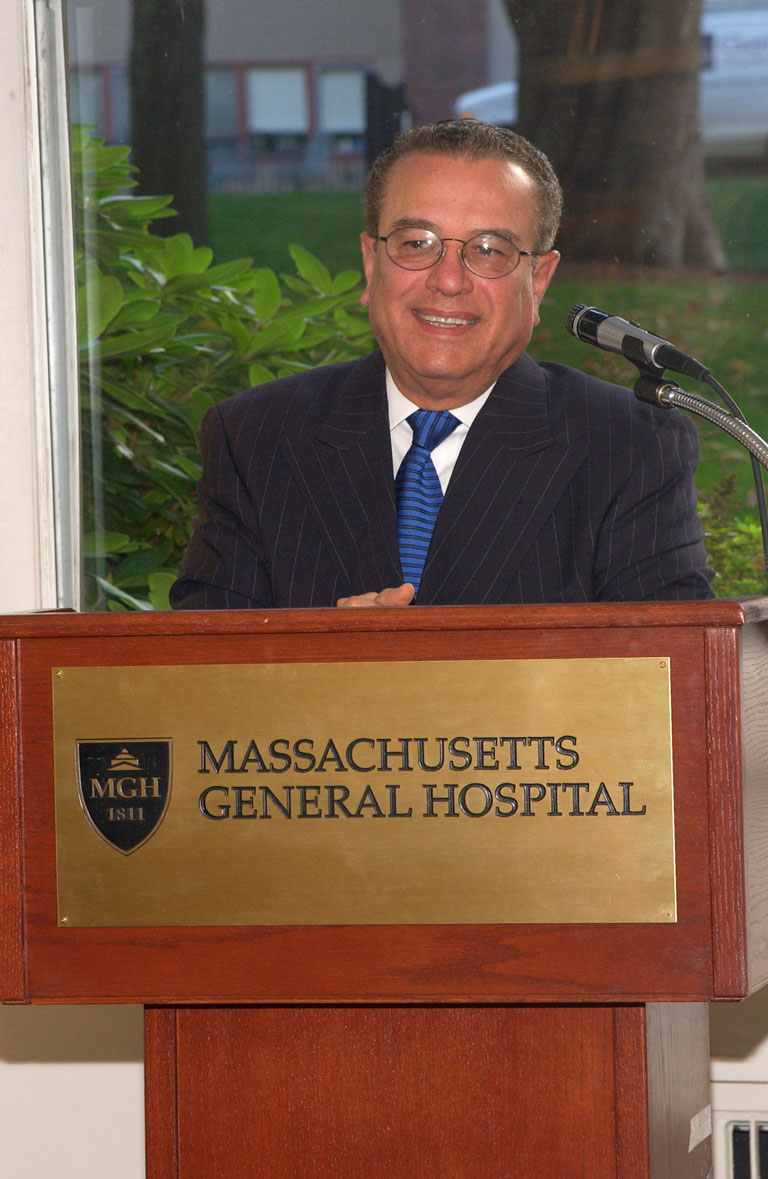

Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez was born in Aquadilla, Puerto Rico, and trained at the University of Puerto Rico. In 1972, Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez graduated from the Dermatology Training Program at Harvard Medical School and later became Chief of Dermatology Ambulatory Services at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez established the first Hispanic Medical Students Mentorship Program in the country, reaching across all four of Massachusetts’ medical schools. He also served as Associate Director of the Multicultural Affairs Office and as a founding member of the Diversity Committee at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez is a Professor of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School and Dermatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Dr. Gonzalez-Martinez has been awarded the Dr. Jim O’Connell Award by Boston Health Care for the Homeless for his service and treatment of homeless patients.

"So after a year and a half of making a quarter of the salary that a person with the same experience and the same education was making I said, “This is discrimination. I cannot.” Then that’s when I think I really started to think about medicine."

"So I was one of the lucky ones that was accepted to go into medical school at the University of Puerto Rico. As a matter of fact, at the end of my four years of medical school, only 35 of us graduated, so 15 did not graduate. Either they couldn’t do it or they decided medicine was not for them and quit early on in their educational career."

"And I remember a case that I always use as an anecdote was a patient that I used to see at the MGH when she had a home...But when I saw her at the homeless shelter…she told me, 'Doctor, I will never go and see you at the MGH because I feel ashamed that I am now homeless and I used to go and see you when I had a home and I had economic situation better than I have now.' And I said, 'Don’t worry. I can see you here every month.'"

"And from here on every year there will be Ernesto Gonzalez Award for community service and we’ll identify every year an employee at the hospital that more or less have gone beyond the duties and recognize that person and there will be a monetary component to the award that is given"

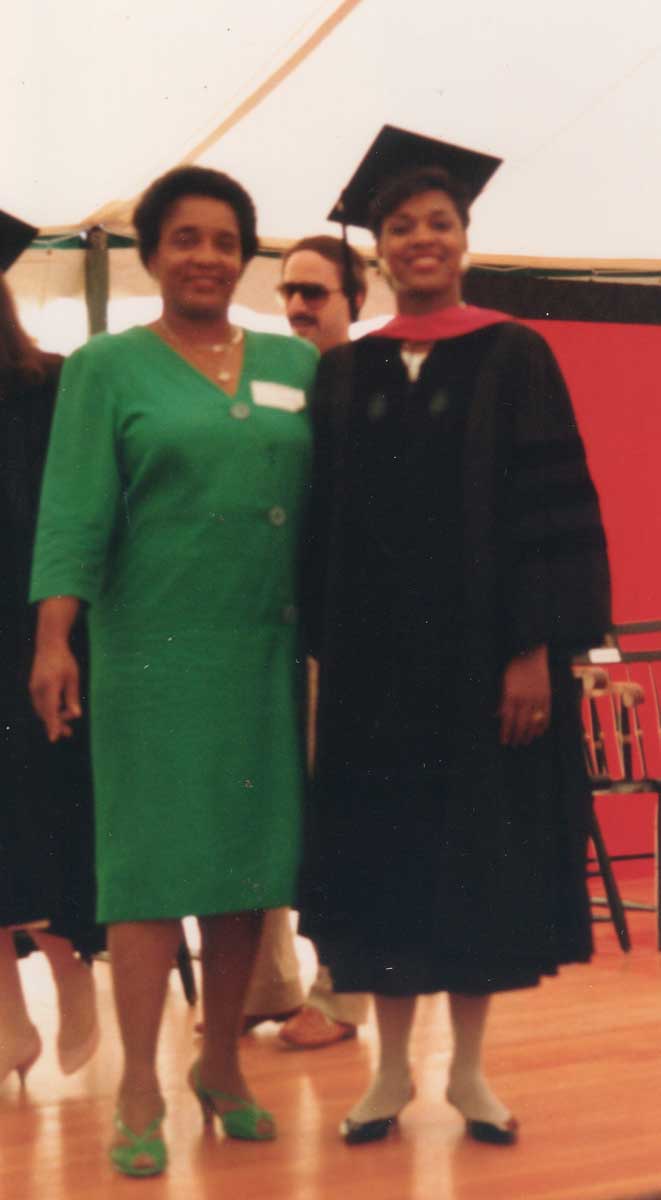

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1973

Shirley Marks, born and raised in Tyler, TX, attended Spelman College in Atlanta, GA. She attended Harvard Medical School from 1969 to 1973, and credits her recruitment to Dr. David Potter at Morehouse College, where she took most of her classes.

Dr. Marks was the second African-American woman to attend Harvard Medical School, graduating in 1973. In 1975, Dr. Marks graduated from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health with a master’s degree in behavioral science. After completing her medical education and training, she returned to Texas, where she specialized in psychiatry.

"Harvard Medical School has accepted Morehouse men for years, for decades; this is not new... I'm the first Spelman graduate to have been accepted at Harvard Medical."

"What happened in September of 1969, the history is, that was the first year that Harvard Medical School admitted more than 3 black students ...And so, we made history; there were 16 of us. I had no idea I was going to be the only female, speaking of social, cultural shock."

"I think that was really the difference, that there was a time when we got together to form coalitions, and when you form coalitions, you find out what other people are doing, whereas before...whoever was there in the 50s, it was just an individual accomplishment."

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1974

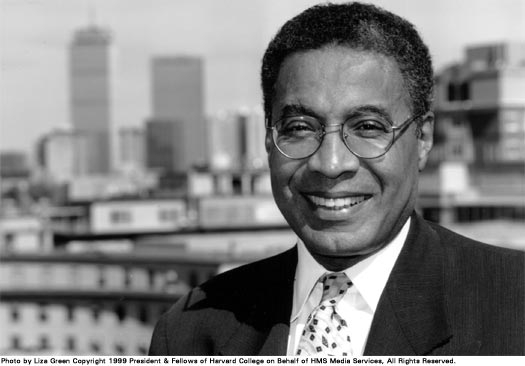

Dr. Talmadge D. King Jr. is dean of the University of California San Francisco Medical School. He grew up in Darien, GA, and attended Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, MN. After attending the Pre-Summer Matriculation Program—where he met and worked with Dr. Alvin Poussaint, Dr. Edwin Fushpan, and Dr. David Potter—Dr. King attended Harvard Medical School beginning in 1970 and earned his medical degree in 1974. Dr. King's research has focused on inflammatory and immunologic lung injury. His bibliography comprises over 300 publications and he is a member of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Association of American Physicians, American Clinical and Climatological Association, and the Fleischner Society. He is a Master of the American College of Physicians and Fellow of the American College of Chest Physicians.

“I grew up and went to school in a segregated, small school in Darien and graduated from high school there in 1966.”

“My interest in medicine probably started early, but I didn’t articulate out lout that I wanted to be a doctor until I was in college.”

“I did the Harvard Health Career Summer Program in, I think it must have been ’68, or ’69, … that was when I met Alvin Poussaint, and Furshpan, and Potter.”

“At the time, the big issues were school busing, and integration in Boston, and it was at a time when it was pretty tense living in Boston as a black person.”

“I always realized that I had to actually work hard and keep pushing so that I could catch up and begin to excel in my work, and so I spent a lot of time studying, and paying attention.”

“I think I started off thinking that I would want to do general surgery, but honestly, I didn’t find a surgeon that I could connect with and liked until I was a senior, and then by that time I decided I would do internal medicine.”

“Because I knew what I knew, and I worked hard to learn what I didn’t know, I actually realized that I could do as good a job as anybody, so I just kept going.”

“And you know, I try to carry with me, carry forward the kindness that they showed me in the work that I do now.”

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1976

J. Emilio Carrillo, MD, MPH, was born in Cuba and came to the US as part of the US government’s Pedro Pan program, which brought approximately 16,000 Cuban children to the country without their parents in the early 1960s. He attended Columbia College in New York City and earned his MD and MPH degrees from Harvard Medical School and the Harvard School of Public Health, respectively. He trained at Massachusetts General Hospital and Cambridge Hospital in the field of internal medicine.

He is currently a clinical associate professor of medicine at the Weill Cornell Medical College and clinical associate professor of epidemiology and health services research at the Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences.

“So as soon as I came to Harvard, I realized that I was among the very first Latinos to come to medical school at Harvard.” (06:50)

“And in 1961 before the missile crisis, there was an opening for children to get out of the country, because there was no visas for adults. So I was one of what’s called Peter Pan -- Pedro Pan -- kids -- about 16,000 young Cubans that left…with their parents staying behind.” (00:35)

”I also spent time doing community health volunteer work. There was a community service council at Columbia that got students involved in community work…I got very involved in working with the local community, working on housing issues, the squatter issues, and really learned a lot about the social determinants of health.” (04:42)

”It took a lot of daring by people like Furshpan and Kravitz and Poussaint and Eisenberg to begin to make the point that minority students had a place in medicine and a place at Harvard.” (10:00)

”And we had a saying that we passed on from year to year, which is that we don’t want to become Harvard-ized. And that terminology kind of meant that we don’t want you to just become a stereotypical Harvard academic -- we want to maintain our community roots, our community involvement.” (32:42)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1979

Andre L. Churchwell, MD, graduated magna cum laude from the Vanderbilt School of Engineering in 1975. He attended Harvard Medical School and earned his medical degree in 1979. He completed his internship, residency, and cardiology fellowship at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, GA.

Dr. Churchwell is a professor of medicine (cardiology), professor of radiology and radiological sciences, professor of biomedical engineering, and Senior Associate Dean for Diversity Affairs at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. He served as Vice Chancellor for Outreach at Vanderbilt from 2020 until he stepped down 2023, transitioning to the role of Senior Advisor on Inclusion and Community Outreach at Vanderbilt. Dr. Churchwell delivered the 2022 Howard, Dorsey, Still Lecture at the Diversity Awards Ceremony at HMS.

“…there was no other med school in the country I was more interested in than Harvard, because it had all those great resources, all the opportunities to look at engineering in medicine and science.” (17:20)

“…my dad’s family originated from a plantation -- which we found out about recently -- down near Clifton, Tennessee, which is in the southwest part of the state.” (00:04)

”And I came home -- been back home since 1991, and have been working with Vanderbilt all along. I…became a dean of diversity involved in diversity since ’07 -- almost 10 years now -- here, taking all the lessons I had learned at Emory -- and the lessons about the importance of diversity from Harvard Med School. Make it clear, I learned a lot about the importance of diversity, and the value of it.” (33:44)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1979

Eve Higginbotham, MD, was born in New Orleans, LA. She studied chemical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and earned her undergraduate and master's degrees there as well. She earned herMD from Harvard Medical School in 1979.

Dr. Higginbotham specializes in ophthalmology and chaired the Ophthalmology Department at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Later, she held positions as dean and senior vice president for academic affairs at Morehouse School of Medicine, and as senior vice president and executive dean for health sciences at Howard University. Currently, she is the Vice Dean for Diversity and Inclusion at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

“And so, I remember those moments as times when I was really proud of my class, that there were people in my class that believed in social justice, who believed in something bigger than who we are.” (23:28)

“…it was just a horrible editorial. And it instantly kind of put me in this -- the spirit of wanting to fight back, to prove him wrong, to really raise a voice against this statement..” (16:20)

”And I just felt that ophthalmology…wasn’t ready for a woman chair...But I decided to take on the challenge, and became a chair at University of Maryland, and that gave me the opportunity to make a mark in my field, as the first woman to chair a university-based ophthalmology department.” (36:49)

”But Harvard Medical School has been a great launching pad in medicine. And I think, even if my experience wasn’t the most ideal, it certainly is irreplaceable as a secure launching pad into a career that I have enjoyed, over these last, almost 40 years, if you will.” (45:32)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1979

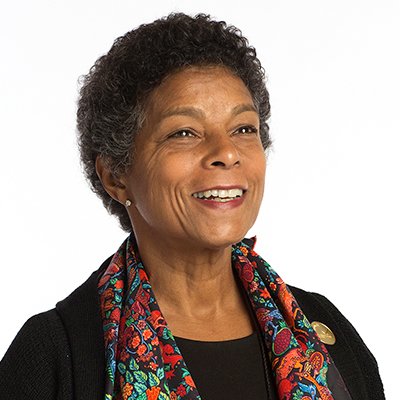

Risa Lavizzo-Mourey was born in Seattle, WA, and earned her undergraduate degree at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. She earned her medical degree from Harvard Medical School in 1979 and her Master of Business Administration from the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business in 1986.

Dr. Lavizzo-Mourey joined the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in 2001 and served as its first woman and first African-American President and CEO from 2003 - 2017. She is now the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation PIK Professor of Health Policy and Health Equity at the University of Pennsylvania.

“And I can still remember that to this day, that that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine that people like me would leave a swath of death in their path.” (11:48)

“So my family was part of the great migration, as it’s often referred to, of African Americans from the South to the West and the North.” (00:50)

”…we went to rent an apartment and as soon as the landlord saw me he said, “It’s rented,” so that’s the backdrop against which coming to the medical school as a person of color…what we found when we got there.” (09:02)

”When I was at Penn as a professor, my primary care practice was making house calls, so I saw firsthand how, where people lived affected their ability to regain health or maintain health…” (17:35)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1979

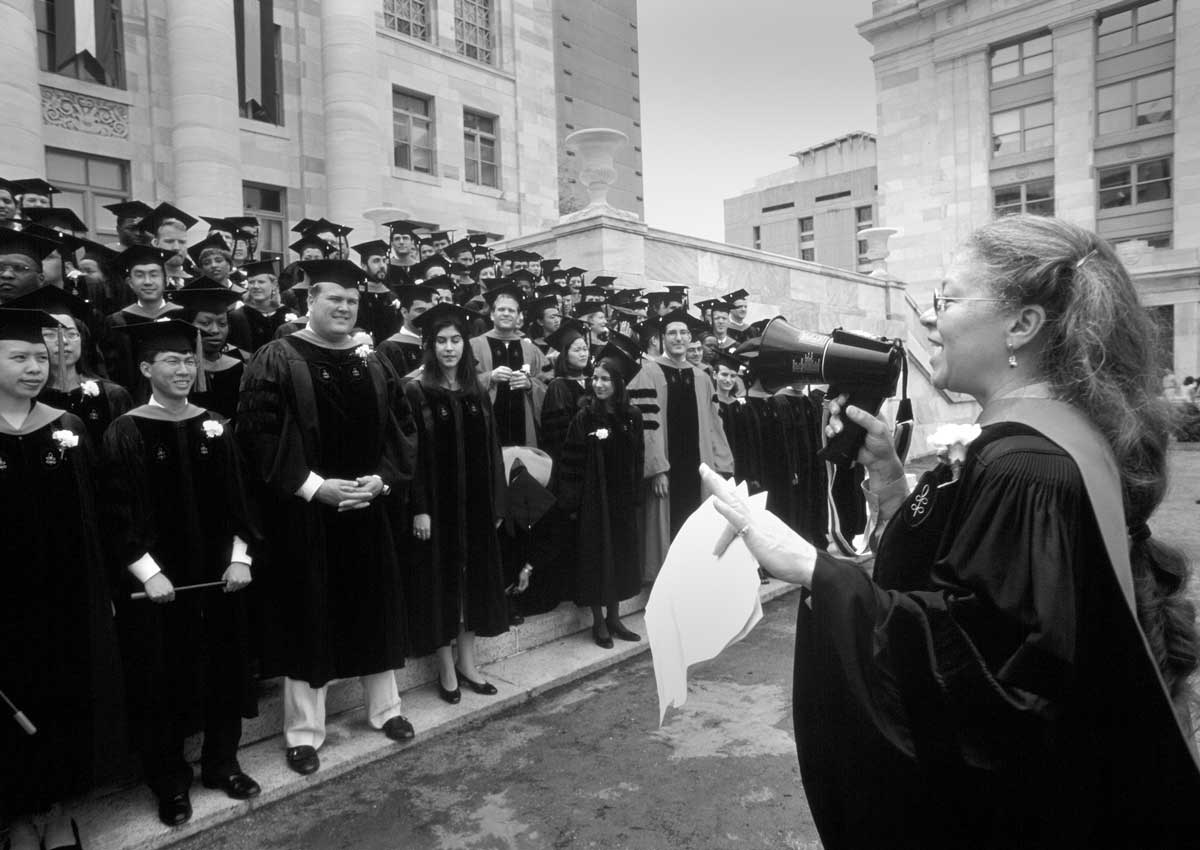

Nancy Oriol, MD, was raised in Philadelphia, PA, and attended Boston University as an undergraduate. She earned her MD degree from Harvard Medical School in 1979.

From 1984 to 1997, Dr. Oriol was the director of obstetric anesthesia at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. She is known for developing the "walking epidural," an anesthetic technique which allows laboring women to move, as well as the NEO-VAC Meconium Suction Catheter for newborn resuscitation. She is associate professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School. She is currently the Faculty Associate Dean for Community Engagement in Medical Education.

Dr. Oriol is also a founder and executive director of The Family Van, a public health outreach program that brings services from the hospital out into the community.

“To have a senior faculty say you all got in through the back door was extremely damaging”

“…in obstetrics, you have everybody, rich and poor, you know, one room next to each other, and everybody -- everyone’s doing the same thing, but you can see the world that comes with them.”

”…so that’s kind of where the Family Van came from… I figured if we went out there and checked people’s blood pressure and dip stick their urine and told them about WIC, that was half the job. Obviously, it was more than that, but that was where it started, it was sort of like how to get education and resources to the people who didn’t even know to ask for them.”

”…so when Joe Martin came here he was very interested in opening the school to the community. So I thought that was a beautiful thing, that he actually cared, he was the one who opened the doors to the community, supported all the community service stuff that was going on, and there was a moment where this was becoming much more community focused in a very nice way.”

”Well the number of minority students was also a line that was increasing but the number of minority senior faculty was decreasing. And so if you have -- if you look at women and you say, more women students, more women faculty. That makes sense. More minority students, less minority faculty.”

”And so it had sort of gone from affirmative action to let people in the front door at all, to caring about disparities and health outcome, like we ought to do something in the sense of social justice, do the right thing -- to the sense of, well we ought to do the right thing and do it well, until cultural competence.”

1983—today

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1984

Lisa I. Iezzoni initially enrolled in a master's program in Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She was interested in patient care in addition to global health policy, so she enrolled in Harvard Medical School.

During her first year of medical school, Dr. Iezonni was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS). She completed her medical degree and went directly into research rather than internship. Dr. Iezzoni became the first woman to be appointed as a professor in the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel Hospital in 1998. She is now the Director of the Mongan Institute for Health Policy at Massachusetts General Hospital.

"The Americans with Disabilities Act was signed on July 26th, 1990…all of a sudden now, people with disabilities had civil rights. And what happened to me back then could not possibly happen to a Harvard medical student now."

"But what happened that summer when I was taking the two inorganic chemistry semesters was that I’d be jogging along the Charles River, because I liked to be very physically active, and I didn’t know where my legs were in space."

"I had a spinal tap. And at the end of that month, I was diagnosed with MS."

"Now, this was back in January of 1981…this was the first time that I realized that this new diagnosis is going to carry implications beyond my health; it’s going to carry implications for how people are going to treat me and react to me…"

"And he paused and he kind of steepled his fingers and he said, “Well, there’s too many doctors in the country right now for us to worry about training a handicapped physician…"

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1987

Georgia native Valerie Montgomery Rice attended the Georgia Institute of Technology, where she received her bachelor's degree in chemistry. She studied medicine at Harvard Medical School and graduated in 1987. In 2011, she became Dean and Executive Vice President for Morehouse School of Medicine.

“Well, the decision to go to medicine, as I said, was impulsive. And so when I came back, after my co-op experience, with this job opportunity offer in hand and recognizing that I didn’t want to be an engineer, I went over to Spelman College -- because at that time, Georgia Tech did not have a formal premed program -- and told them my idea that I thought I would go to medical school.”

“I wanted to do reproductive endocrinology. And what really was the key ingredient that probably enticed me... So I did that rotation toward the end of all my rotation. Because I thought, for sure, that I was going to be a neurosurgeon, when I went to medical school.”

“I think about the things that probably made the biggest difference for my experience at Harvard Medical School -- was that I felt very supported. So I felt that there was clearly the opportunity to do anything that I wanted to do.”

“When I started working in women’s health, I started working as an advocate for women of color -- looking at how they were disproportionately not represented in clinical trials, looking at diseases that disproportionally impacted women of color based on their reproductive function or endocrinological function.”

“I think I had a very great experience at Harvard Medical School, so much so that, you know, my daughter’s a first-year student there -- so she’s in the first-year class now at HMS. And what I believe that Harvard Medical School allowed me to do was to blossom. It affirmed for me what was possible through hard work.“

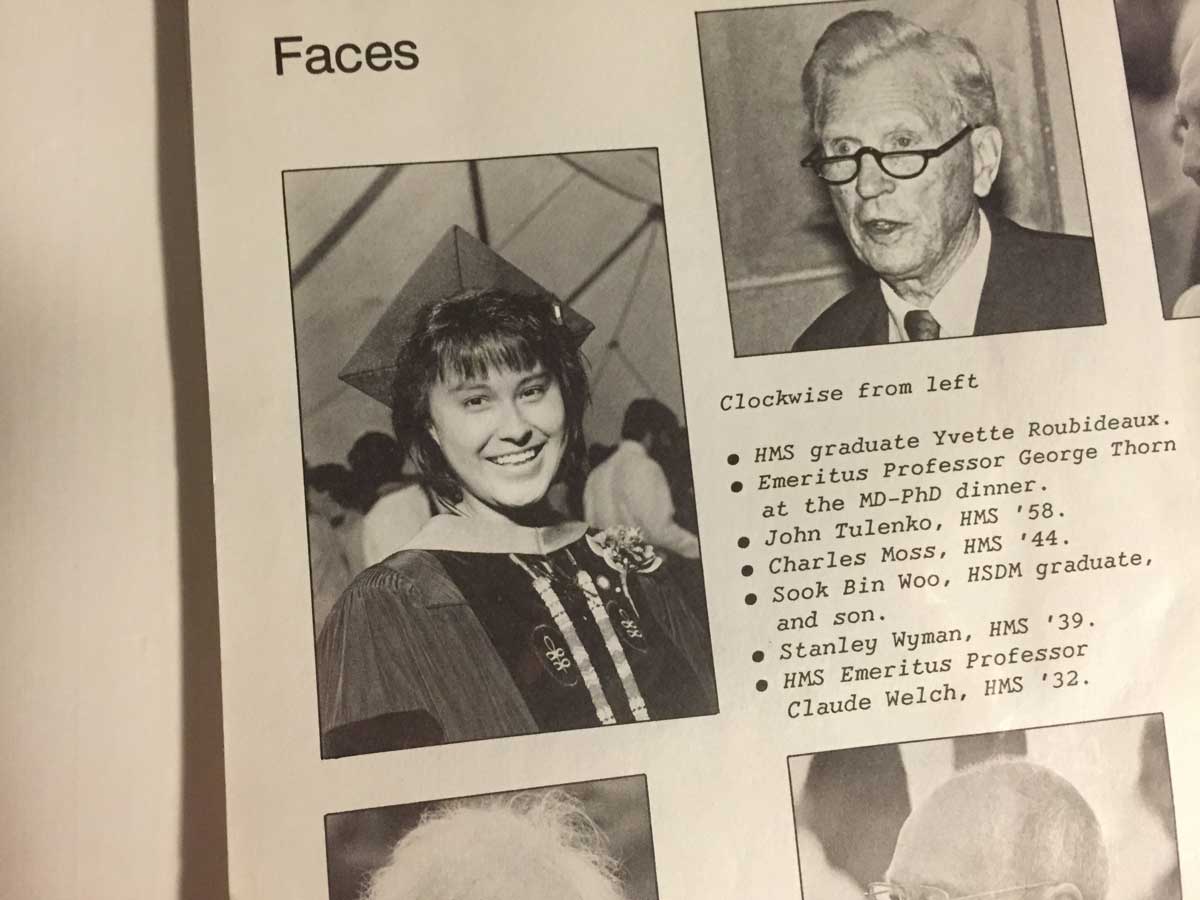

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1989

Yvette Roubideaux grew up in western South Dakota, and is a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. She attended Harvard College and graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1989. She also completed her Master of Public Health degree at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Dr. Roubideaux worked in clinical practice for the Indian Health Service, conducted extensive research on American Indian health issues, and was appointed as the Director of the Indian Health Service in the administration of President Barack Obama in 2009. She was the first woman to serve in this position.

“I am a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. And also Standing Rock Sioux. … I first decided to become a doctor when I was thinking about careers in high school. And I recalled the incredible need that there was for doctors in the Indian Health Service.”

“I have known from the day I decided I wanted to be a doctor that I wanted to go back and practice medicine in the Indian Health Service. I wasn’t sure what kind of doctor I wanted to be, except that the doctors they needed were primary care doctors. And Harvard didn’t have a family medicine rotation.”

“A faculty mentor told me, or said the line, “You know, it’s a shame you’re wasting your Harvard education if you’re only going to go back and work on an Indian Reservation.””

“It was really a turning point for me to say, well, you know, obviously that faculty mentor did not understand the need, and did not understand that American Indian/Alaskan Native patients deserve the best trained doctors. And actually, they probably deserved more better trained doctors because of the complexity of their situation and their illnesses and the challenges and the system.”

“Back in the 1980s, there was always the unspoken fear that people thought that we were admitted because of our race and not necessarily because of our potential or our skills.”

“So, for me, it feels like … -- whenever I visit Harvard, it feels like the climate is so much better. There’s a lot of work to be done.”

“I became very interested in, you know, the challenges of diabetes in American Indians. But I also saw the limitations and the frustrations of working in an underfunded system.”

“In 2009, I got the call to join the Obama Administration, and was nominated and Senate confirmed as the Director of the Indian Health Service.”

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1990

Dr. Carmon Davis is a pediatrician in general pediatrics at Boston Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Davis earned her MPH from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in 1994. She was the President of the Harvard T. H. Chan Alumni Association from 2019 to 2021. Dr. Davis’ full oral history is available to researchers at the Center for the History of Medicine. Contact chm@hms.harvard.edu for more information.

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1993

Dr. Valerae O. Lewis grew up in the Bronx, New York City, and, from a young age, wanted to be a doctor. She attended Yale University, where she graduated with a degree in Psychobiology. She graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1993 with honors and completed her orthopaedic training at the Harvard Combined Orthopaedic Residency Program.

Since 2000, Dr. Lewis has been at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, where she continues to be a trailblazing figure in medicine. She was named the Dr. John Murray Professor in Orthopaedic Oncology in 2010. She was the first African-American woman to be awarded the MD Anderson Faculty Achievement Award in Patient Care (2012); first woman to chair an orthopaedic department at a freestanding cancer center (2014); first woman to chair an orthopaedic department in The University of Texas System (2014); and the first African-American woman to chair an Orthopaedic Surgery Department.

“I never wanted to be anything else but a doctor. I mean, I will say that I wanted to own a gas station, and I wanted to be a carpenter on weekends, but I always knew that I wanted to be a doctor. … My dad …still made house calls probably till his late seventies.”

“So I remember mailing in the Yale postcard and putting no on the Harvard one. And then I came back to my -- the car, and my mom asked where I said I was gonna go, and I said Yale. And she just started crying, and she goes, “I just wanted one of my daughters to go to Harvard!” So I felt really bad, ’cause it was probably a silly argument, and so I said, “OK, I promise I’ll go to Harvard Medical School.””

“So one of the things I remember is you’re applying to residency program, you know, and as a women -- woman, and as an African American woman applying to orthopedics, it can be a little daunting ’cause it’s generally all white male. And I remember I read the -- one of the recommendations from one of the orthopedic faculty, and just the last -- the last paragraph, but it was glowing. And it just made me feel like I can do this, like I am just as good as the rest of these boys out here.”

“Harvard’s orthopedic program is actually a combination of Mass General, BI Deaconess, Brigham, and Texas Children... And that was a great residency. It was a very diverse residency, compared to other residencies at the time. There was at least one to two women a year, and one to two African Americans or people of color a year. Really, we have Gus White and Henry Mankin to thank for that.”

“I really started as assistant professor and worked my way up to become the John Murray Professor of Orthopedic Oncology, but also chair of an orthopedic oncology department. And it was exciting, ’cause there are no other black women chairs of orthopedics, and there aren’t any other women chairs in surgery in the whole UT system, and UT system is very large. “

“But what’s interesting is -- and I included it in my talk -- all the stories, or many of the stories, of the African American physicians back in the early ’60s, you know, even early ’20s, the obstacles they’d face are still present with many of the African Americans today.“

“As I get older, you realize the importance of including and bringing up more people like yourself, because as you get higher and higher in the administrative echelon you realize there are fewer and fewer people who look like you. And then you combine that with all the studies that show that diversity breeds innovation, and innovation breeds success, that you’re even more encouraged to go and make a diverse workforce or a diverse administrative team.”

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1996

Dr. Kathryn Hall is an associate molecular biologist and an assistant professor in the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Director of Placebo Genetics in the Program in Placebo Studies at Harvard Medical School (HMS). After receiving her PhD in microbiology and molecular genetics from Harvard University, she spent 10 years in the biotech industry tackling problems in drug discovery and development, first at Wyeth (now Pfizer) and then at Millennium Pharmaceuticals (now Takeda), where she became an Associate Director of Drug Development. Dr. Hall returned to HMS in 2010 and joined the Fellowship in Integrative Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in 2012. She received her Master of Public Health degree from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in 2014. Dr. Hall was the 2015 Harvard Catalyst Program for Faculty Development and Diversity Inclusion (PFDD) faculty fellow and is the 2019 BWH Minority Faculty Career Development Awardee.

She was awarded a Radcliffe Exploratory Program grant which supported the groundbreaking Placebome in Clinical Trials and Medicine Conference in 2019. Her research has been the focus of numerous articles including features on BBC and in Science, The Atlantic, New York Times, The Economist, and Discover magazines. Dr. Hall also has a master’s in documentary film from Emerson College.

“My goal was to get to industry, so I could, you know, make a company to employ Jamaicans, and we would, you know, become self-sufficient in this pharma industry in Jamaica.” (time)

“I was one of the founding members of MBSH, which is Minority Biomedical Scientists of Harvard.” (time)

“In the first meeting, they called all us graduate students together, I think there were about five of us in my class. And they said, they showed us a graph, and on it, it showed the enrollment, the PhD enrollment, like over the last, you know, 5 to 10 years. And they show it going up, up, up, up, up, and then it just plummets down. And they asked us if we had any idea why it would have plummeted down. And of course, it was exactly the year when Dr. Amos retired.” (time)

“I had registered for a conference here, and in line, and the person is checking me in, and they say to me, “Are you signing in for somebody else?” And I say to them, “What is it about me that makes you think I’m signing in for someone else?”” (time)

“And I thought wow, why don’t I do that, and do all the things I’ve ever wanted to do? And I made a list of the things that I always wanted to do in life, and they were, I always wanted to be a filmmaker, make a, you know, a film. I always wanted to renovate a house. I always wanted to write a book. I always wanted to have my own business.” (time)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 1996

Dr. Thomas Sequist is an associate professor of medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA. Dr. Sequist is chief quality and safety officer at Partners HealthCare, director of the Four Directions Summer Research Program at Harvard Medical School, and medical director of the Brigham and Women's Hospital Physician Outreach Program with the Indian Health Service. He graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1999. In 2019, he spoke at the 50th anniversary celebration of Diversity and Inclusion at HMS and HSDM.

Interview Transcript | Part 1 of 2 (pdf)

Interview Transcript | Part 2 of 2 (pdf)

“It was the fall of my junior year and sort of realized I don’t know that I want to do this I think I might want to go to a medical school.” (time)

“The short answer of like why did I end up at Harvard, is because it sort of felt right to me.” (time)

“The main set of activities that we did back then was something called the Four Directions Summer Research Program... The First summer it ran actually was the summer before I got to Harvard in 1994.” (time)

“One of the big things that has changed is that when we were first running that program way back in the mid-’90s, we were only really a year or two more advanced than the students who were coming here. We had made -- with one big difference is that we had got into medical school, which was really exciting. … So I am now – you know, 25 years later, I am still the primary person who sits down and meets with these students…”(time)

“What I really always had wanted to do when I first was in medical school was, I wanted to become a physician and go back and work in the Indian Health Service on a reservation. And I obviously didn’t do that … maybe I could contribute to the Native communities in different way…” (time)

“I think Boston has changed a bunch over the past 25 years that I’ve been here, but I think it still has a lot of issues to confront… But at the end of the day, if you ask any person of color in this city, Does this feel like a welcoming environment, I think all too often, unfortunately, you’re going to hear, No, it doesn’t feel totally welcome.” (time)

“if you don’t support people who are interested in community outreach -- all of the stuff that Joan Reede’s office supports -- if you don’t support people who are interested in research that’s not in a lab but is interested in research like I do -- like health equity, health policy research -- you are really limiting the type of person who might want to come to Harvard and contribute to our community.”(time)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 2001

Dr. Saldaña is Dean for Students at Harvard Medical School and oversees the Office of Student Affairs. Dr. Saldaña is a clinical cardiologist at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, and Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. He graduated from Harvard Medical School in 2001.

“My job was to be a student. Growing up, they said, “Work hard in school,” because my parents didn’t have a chance to go to school, so that’s something that we really valued growing up, and I think that’s probably what led me to pursue a career in medicine.” (time)

“As a kid you’re kind of always at the bottom of the totem pole, of the hierarchy, and having this special talent of speaking English … So I think feeling like I had a special talent as a kid, where I could help, and I would help random people too… I would translate for random people on the street. And I thought that was something very special I could use to help others, my mom really kind of instilled that idea of helping others and generosity and looking out for one another.” (time)

“I met some great mentors, and eventually I found a little niche in that group that was called Chicanos in Health Education. Students that were of very similar background who had the same dream, and really we supported each other, and all of us really were successful in getting into medical school…” (time)

“I’ve seen ups and downs, to be honest. As a student I felt that |LS|diversity and inclusion] was always valued.” (time)

“But I think it’s always a challenge that we hit certain ceilings that we haven’t been able to go above. And I think that’s probably the next step, is how can we make sure that all of our institutions have best practices, and how can we break some of those ceilings.” (time)

“But you can’t really do without all the mentors out there so maybe if anybody is listening or reading, |LS|I’m] just encouraging |LS|you] to reach out to folks, because you will make an incredible difference in someone’s life.” (time)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 2004

Dr. Washington is an associate clinical professor at the UC San Diego School of Medicine in the Department of Reproductive Medicine. Dr. Washington also works as an abortion provider at Planned Parenthood and was formerly the Medical Director and Chief Medical Officer of Planned Parenthood of the Pacific Southwest. She graduated from Harvard Medical School in 2004.

In 2001, student Sierra Washington co-founded FABRIC, an annual event celebrating the diverse backgrounds and talents of students in the Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Dental Medicine community. Originally founded to explore the artistic and cultural traditions of the African diaspora, FABRIC has evolved through the years to include art forms and cultures from around the world. First-year students perform during Revisit Week and invite newly admitted students to join the community at the two schools. For more information about FABRIC visit: https://hms.harvard.edu/news/show-welcome.

“I had a lot of difficulty assimilating into the United States, mostly because the way that people conceive and conceptualize race really informs all of society, and I just wasn’t really ready for that. So I had a pretty tough time in university understanding how race just could permeate everything, everything that you do, and I felt a lot of pressure on campus to conform.” (time)

“I think I knew from very early on that I was going to go into medicine.” (time)

“After my trip to Thailand, it felt like, you know, I just, I know I want to do something in the world to alleviate poverty and suffering.” (time)

“The reason I ended up choosing going to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is because I knew I wanted to work in Africa, and I knew I wanted to do work on HIV.” (time)

“I hated internal medicine; I hated it so much. I felt like, first of all, the nurses were mean and racist …, and treated me horribly. And second of all, I did not like the culture of like, OK, we spend five minutes with the patient, and then we sit in a room, a conference room, and discuss for hours, you know, should we do this, or should we do that? Is it this, or is it that? … I almost dropped out of medical school after that.” (time)

“I remember writing home and saying, like, this is 2000, and women are still dying in childbirth for no reason, you know, other than like, there’s just not enough resources being put to it.” (time)

“I just remember feeling like, you know, this is like a very impoverished side just on the backside of the hill, and you know, we’re right next to these ivory towers; it’s kind of crazy. One day I stopped into this school, and there was this guy who was like, yeah, I’d love for there to be an afterschool science program for young girls.” (time)

“We kind of started this curriculum project, and through that, we had this idea of like, maybe we should fundraise for a specific disease that strikes the black community. And, being an artist, I was like, why don’t we do an art show? Why don’t we showcase the fabric of the black community here in the Longwood area, because so many people, as I mentioned earlier, came to Harvard with already this incredible talent in something else, and decided to do medicine.” (time)

“How does that exist in 2000? Like, this is like, you know, this is pre-civil rights style segregation. And then that was borne out in the hospitals.” (time)

“Harvard’s no different than any other institution in having those things happen, other than it’s been around longer and has more entrenched this white privilege.” (time)

“And that was a mind-blowing experience, because things like, why was it easier for women to get an IUD in Rwanda than in the Bronx?” (time)

Graduated Harvard Medical School Class of 2018

Dr. Tate graduated from Harvard Medical School in 2018 and served as President of the Harvard Medical School Chapter of the Student National Medical Association. Dr. Tate also hosts, produces, and edits the Dear Premed podcast and was a fellow for One Heart Worldwide, a nonprofit that implements maternal and neonatal mortality prevention programs in areas where women often die alone at home giving birth. Dr. Tate graduated from Dartmouth College in 2012 and is currently an OBGYN Resident at McGaw Northwestern.

“I’ve known that I wanted to be a doctor since I was a little girl. More specifically, I knew that I wanted to be an obstetrician.” (time)

“I was the director of a program called the Dartmouth Alliance for Children of Color, where we brought children who were African, or African American children, mostly children who are adopted into white families, in the Upper Valley area, who come to our school once a week and they hang out with people that look like them.” (time)

“I learned about this organization that was doing work to reduce maternal, or you know, maternal and infant mortality, morbidity, things that were preventable. So they specialize in working in very remote and rural areas around the world.” (time)

“What does it mean for my community to be able to have been trained at Harvard Medical School, you know? That was a big part of my calculus in deciding to come here, and thinking about how I could then use this platform, use this privilege, for the communities that I care about.” (time)

“In my entering class, we came in together, 15 students, and said that we’re just going to make this place what we want it to be. We’re going to make this community strong, and we’re very intentional, and very deliberate about that.” (time)

“We also wanted to make sure that our voices were heard here at the medical school, and across all different levels of the administration.” (time)

“For them to just light up when they see this black girl walking in the room with the rest of her team, which usually was mostly white, and to just look at me with such pride, and such joy in their eyes.” (time)

“I think that the medical school has also done a good job of recognizing that we’re not where we need to be, and so, we have to figure out what to do to make it better.” (time)

“I want my work to center around racial and ethnic inequities in birth outcomes. So whether that’s maternal mortality or infant mortality, or morbidity in either of those things, I want that to be the centerpiece of the work that I do.” (time)